What an Existential Retreat Taught Me About Me

I’ve carried a vision for years—a hope to grow existential therapy in Singapore beyond the therapy room. Not just as an approach for individuals in talk therapy, but as a way of living, relating, and becoming. A space where we understand ourselves arise not by turning further inward, but by going outward—into movement, into sound, […]

Emerge and Evolve An Embodied Existential Retreat

📅 Choose one: Sunday, 14 September or 20 November 2025 🕣 8:30am – 6:30pm 📍Aliwal Arts Centre 💰 $300 early bird (before July 31) / $350 regular Maybe you don’t always find the right words. Maybe reflecting alone hasn’t brought you closer to who you are. This retreat is for you. Emerge and Evolve is […]

What My Dog Taught Me About Being in This World

Recently, I faced one of the hardest moments of my life. My beloved dog, Guinness—the first baby girl of our family—was diagnosed with cancer. The photo above is the last one we took together. Hearing the news was devastating. I was shocked. Then came the painful realization: Our time together will now be heartbreakingly short. […]

Saying “Yes, And”: Setting Boundaries Can Be More of a Dance Than a Stance

Are you ready for the lifelong waltz between discomfort and liberation? I recently started participating in Playback Theatre as a novice performer. In this form of improvisational theatre, the audience tells stories and watches them enacted on the spot, where most of the performance is spontaneous. As a general rule-of-thumb for the performers, we will […]

Why Are My Therapy Sessions 50 Minutes?

Why are weekly therapy sessions 50 minutes? Why not more, why not less? I often get that question from clients. Here’s what I tell them: Having a set time allows for the client to think about how they want to use that time. Do they want to talk about 10 things or focus on just […]

I lived Through a Life-Enhancing Anxiety Moment.

It was my first time sharing about existential therapy to a large audience in Singapore at the National Counselling & Psychotherapy Conference 2023. I have shared my study on [authenticity and silence in the Asian society] multiple times before—in groups, one-on-one sessions, virtually, and in writing—but never in such a large setting, addressing an audience […]

We Are Called to be Responsible For Our Voices.

I’m so glad this CNA commentary came up. It says something about our voices. As we find our voices as Asians, we also need to think about taking responsibility for our voices. Rightfully pointed out by Jonathan Kuek, there is “a fine line between trolling and calling someone out.” Existentialism challenges us to confront the […]

We Can Have Many Different Ways of Living

Tan Kheng Hua was a familiar face in my younger years and for many Singaporean millennials. I remember growing up and watching her on TV in Masters of the Sea and Phua Chu Kang. She was also in some of my all-time favourite productions by Wild Rice and TheatreWorks: Animal Farm, The Eleanor Wong Trilogy: […]

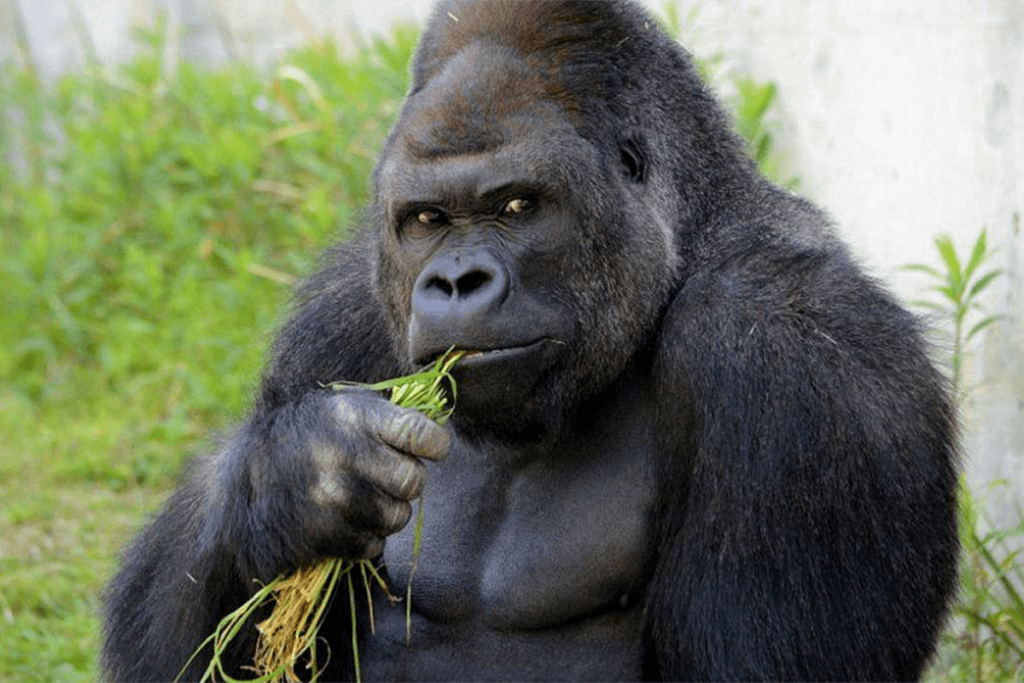

Your Presence Matters

How does this gorilla appear to you? The first time I saw Shabani, I felt a connection; his gaze conveyed an understanding of the person taking the photo and their existence. The eyes seemed so soulful, expressing emotions, intentions, and empathy. Notice the whites of Shabani’s eyes? He has that distinct white sclera, exactly how […]

Existential Therapy: Finding the Light in the Darkness

You may be thinking, from what I know about existential therapy, it sounds negative, dark, heavy, pessimistic and/or depressing. I’m not sure if it will make my life more depressed and anxious than I already am. It’s true that existential psychology acknowledges the inherent suffering in human existence, but this is not a call to […]