What an Existential Retreat Taught Me About Me

I’ve carried a vision for years—a hope to grow existential therapy in Singapore beyond the therapy room. Not just as an approach for individuals in talk therapy, but as a way of living, relating, and becoming. A space where we understand ourselves arise not by turning further inward, but by going outward—into movement, into sound, […]

Saying “Yes, And”: Setting Boundaries Can Be More of a Dance Than a Stance

Are you ready for the lifelong waltz between discomfort and liberation? I recently started participating in Playback Theatre as a novice performer. In this form of improvisational theatre, the audience tells stories and watches them enacted on the spot, where most of the performance is spontaneous. As a general rule-of-thumb for the performers, we will […]

Your Presence Matters

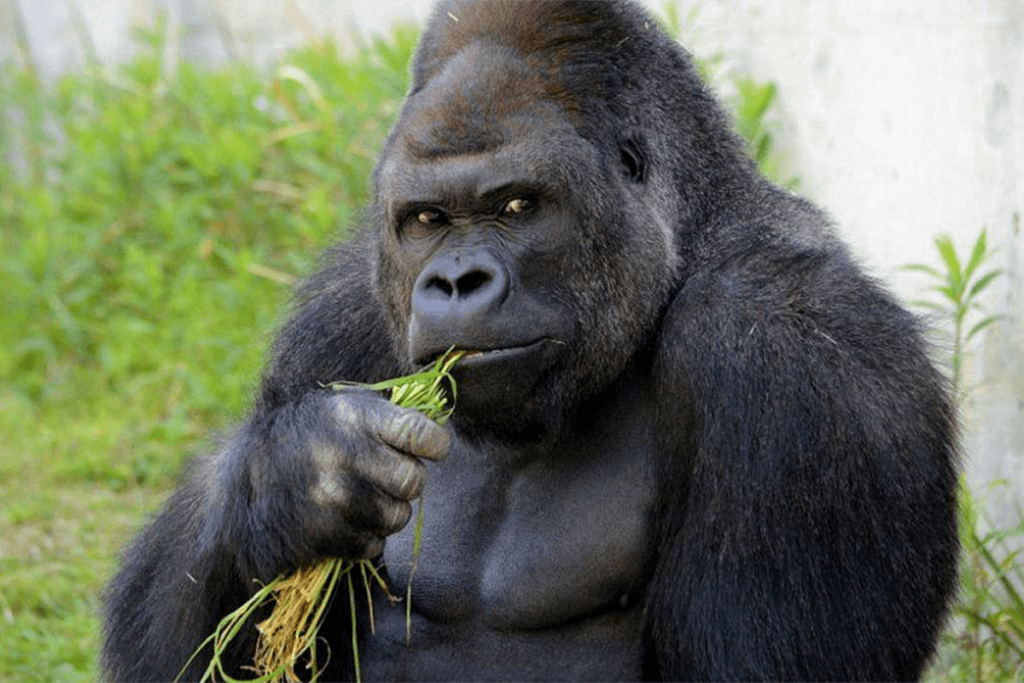

How does this gorilla appear to you? The first time I saw Shabani, I felt a connection; his gaze conveyed an understanding of the person taking the photo and their existence. The eyes seemed so soulful, expressing emotions, intentions, and empathy. Notice the whites of Shabani’s eyes? He has that distinct white sclera, exactly how […]

Existential Therapy: Finding the Light in the Darkness

You may be thinking, from what I know about existential therapy, it sounds negative, dark, heavy, pessimistic and/or depressing. I’m not sure if it will make my life more depressed and anxious than I already am. It’s true that existential psychology acknowledges the inherent suffering in human existence, but this is not a call to […]

What It’s Like to Visit an Existential Therapist

Through the parents of Abigail and Lara, I am reminded of what it means to be an existential therapist. Last Sunday, I read this article about a couple’s fight to have their daughters’ names recognised, even though their identities will not be “in the provision or use of government services throughout their lives”. If there […]

What Do We Already Know About Anxiety?

Let us do a stock take on what we know about anxiety. What is anxiety? Anxiety is a feeling we have when we get worried, tense and afraid about something that is related to our future. It is a human condition that happens when we sense that we are unsafe, exposed, vulnerable, unprotected or under […]

There’s No One Way to Live

You may be thinking, where did existential therapy come from? The philosophy of existentialism has the face of gloomy and depressing post-World War II France and Gauloises- smoking intellectuals furtively discussing the meaninglessness of existence. Many people also associate it with such concepts as nihilism, angst, atheism and death. Existential ideas themselves have a lineage that ‘can […]

Reflections: Why Did I Choose To Be An Existential Psychotherapist?

Why did I choose to be an existential psychotherapist? Over the years, I have been asked this question numerous times . After all, this is a less popular field within counseling in Asia, much less Singapore. Honestly, I have often found it difficult to answer this question. It is not that I do not know […]

How Can Psychotherapy Help Me With My Existential Crisis?

These days, we hear many people talk about feeling bored, tired or even anxious in their lives but not knowing why despite having a comfortable lifestyle. The struggle to experience our life as meaningful or to feel we are living other people’s lives rather than on our own terms can be destructive. It negatively affects […]

Understanding Existential Therapy?

Existential Therapy – Finding the Light in the Darkness You may be thinking, I’ve never heard of existential therapy before. It sounds so negative, dark, heavy, pessimistic and/or depressing. I’m not sure if it will make my life more depressed and anxious than I already am. While it’s very true that due to the existentialist […]