You may be thinking, where did existential therapy come from? The philosophy of existentialism has the face of gloomy and depressing post-World War II France and Gauloises- smoking intellectuals furtively discussing the meaninglessness of existence. Many people also associate it with such concepts as nihilism, angst, atheism and death.

Existential ideas themselves have a lineage that ‘can be traced far back in the history of philosophy and even into man’s pre-philosophical attempts to attain some self-understanding’ (Macquarrie, 1972: 18). Existential ideas, questions and ways of philosophising have been identified in the teachings of such notable figures as Socrates, Jesus and the Buddha (Macquarrie, 1972), as well as in such ancient philosophical systems as Stoicism (van Deurzen, 2002a). Existentialists place great emphasis on in-the-world-with-others nature of human existence. They reject individualism and subjectivism that is inherent in more humanistic approaches.

The roots of existential psychotherapy lie in philosophy from the 1800s, and more importantly with philosophers whose work dealt with human existence. The philosophers most commonly associated with existential therapy are Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Heidegger and Sartre. However, Halling and Nill write, existential therapy ‘cannot be traced to a single authoritative source’, and so unlike other therapies, this approach does not have a common theoretical and practical basis.

You must remember that existential philosophers are diverse themselves. Some are deeply religious (Kierkegaard, Buber, Victor Frankl, Marcel), others are atheistic (Sartre, Nietzsche and camus). Some emphasise individuality (Kierkegaard and Nietzsche), others emphasise the need for relationship (e.g. Buber, Marcel and Jaspers). Some consider existence to be meaningless (Sartre and Camus) while others put emphasis on hope (Marcel). So one can only speak of existential philosophers in the loosest sense as a group of thinkers who ponder about what it means to live.

What is most important is to appreciate the diverse ideas on existence that there is no one single way to live.

We humans are all different. There’s no one way to live.

Several Rich Tapestries

In this century, psychologists started taking these philosopher’s ideas and use them in therapy.

More popular ones include Viktor Frankl who wrote Man’s Search for Meaning in 1946, and coined logotherapy as a method of creating meaning.

Rollo May brought this European perspective to America in the 1950s, giving it a more optimistic flair focused on the vastness of human potential, and called it the “existential-humanistic” approach.

In 1980, Irvin Yalom defined the four “givens” of the human condition—death, meaning, isolation, and freedom—that have become the basis for the field.

Today there remain different branches of existential therapy, but they all help clients face existential givens head-on so that they can move toward a more “authentic” and free existence.

All Of Us Are Unique In Our Relatedness

At Encompassing, our guiding principles come from the British school of Existential Analysis. This was influenced by many existential philosophers such as Kierkegaard, Nietsczhe, Sartre, Buber, Jaspers and Merlaeu Ponty.

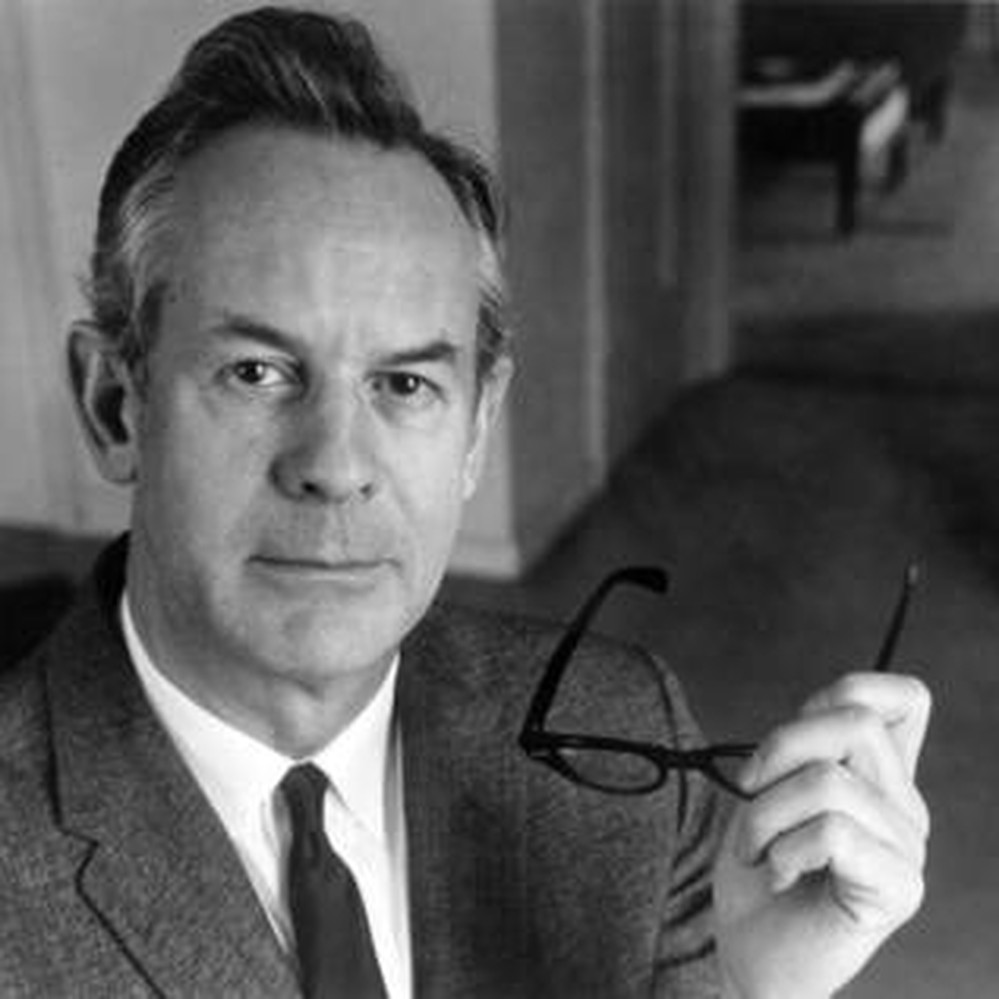

The 3 organising principles in existential therapy are discussed by Professor Ernesto Spinelli, Academic Dean of the School of Psychotherapy and Counselling at Regent’s College, London:

- Relatedness argues that everything that exists is always in an inseparable relation to everything else. From this understanding of relatedness, every thought, feeling and action experienced or undertaken by me is said to arise not only from the interaction of systems and components within me but also between self and others and between self and world. Essentially, we are always in relation and with all other beings. All of us are unique in our relatednes. Each being stands out in a wholly unique and unrepeatable way of being and is able to be and do so through a foundational relatedness that is not only shared by all beings but which is also the necessary condition through which individual beings emerge.

- Uncertainty arises as an immediate consequence of relatedness. Uncertainty expresses the inevitable and inescapable openness of possibility in any and all of our reflections upon our existence. I can never fully determine with complete and final certainty or control not only what will present itself as stimulus to my experience, but also how I will experience and respond to stimuli. At any moment, for example, all prior knowledge, values, assumptions and beliefs regarding self, others and the world in general may be open to challenge, reconsideration or dissolution in multiple ways that might surprise or disturb. Common statements of uncertainty include ‘I never thought I would act like that’, or ‘She seemed to turn into someone I didn’t know’

- Anxiety is a direct consequence of the first two principles in that it expresses the lived experience of relational uncertainty. It is necessary to note from the outset, however, that existential anxiety is not only an expression of disabling and unwanted levels of unease, nervousness, worry and stress. It is much more generally a felt experience of incompleteness and perpetual potentiality which is expressive of an inherent openness to the unknown possibilities of life experience. Existential anxiety can be both exhilarating and debilitating, a spur to risk-taking action as well as stimulus to fear-fuelled paralysis.

This is why, at Encompassing we:

- Stay with the actuality of the client’s lived experience.

- See clients as having ‘problems with living’ rather than having pathological issues that need to be treated.

- Explore different ways of relating to the world – personal, social, physical and spiritual.

- Look at how clients handle paradoxes or polarities. E.g. good vs evil, trust vs distrust, belonging vs isolation, intimacy vs separation, transcendence vs mundanity. Mental wellbeing is found when we are able to be flexible enough to live on both extremes at the same time.

- A lot of dilemmas can be found when we are fixated on one end and refuse to look at the other end possibly because of a lack of familiarity or with too much uncertainty. Our goal is not to help clients find answer to the dilemmas that they bring into the session, but to help them see and accept that living presents us with many dilemmas.

- Focus on choice, responsibility and freedom. For instance: Through such an acceptance, clients can then begin to address the real challenges that face them. For instance, they start to ask questions such as ‘How do I become more authentic to myself even though I know the choices will not make my life easier?’

- Challenge taken-for-granted assumptions and are open to a multitude of perspectives.

The primary value of existential-phenomenological thinking for therapists is that it offers them a way of being which they can come to embody, rather than providing a frame-work by which to understand clients, or as a blueprint for living.

Resources

Spinelli, E. (2015). Practicing existential therapy: the relational world. (2nd ed.). London, SAGE Publications.

About the Author

Hi, I'm Mag: a UKCP-accredited counselling psychologist and founder of Singapore’s first ever existential practice. My care philosophy is not to diagnose, label, or categorise but rather to work with the individual in front of me in the here and now.

My clinical credentials certainly play a significant role in defining my professional identity. But to foster a deeper connection and authenticity, I invite you to discover my other “Selves”, the various facets of who I am.