Most of my friends secured jobs before graduation and began working immediately afterwards. Although I felt the pressure to do the same, it did not sit right with me to do so. I wanted to discover a path on my own terms.

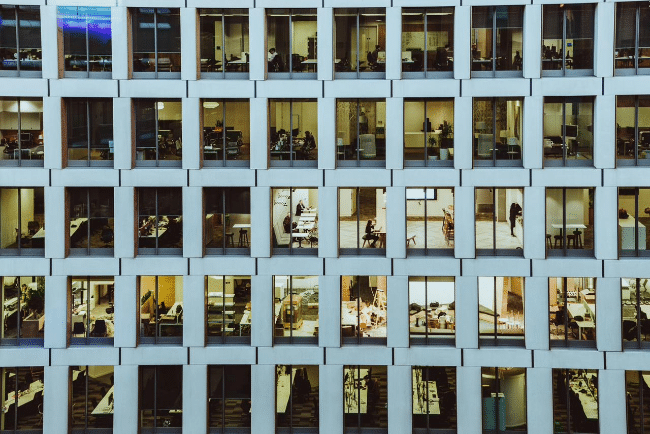

For one, I was scared to enter the “real world.” I did not feel ready for a world of grown adults being cut-throat about maintaining their self-interests while wearing a mask of niceties for deception.

What am I scared of? Losing myself—while pursuing things I don’t actually want and value, things that do not bring me joy and contentment.

In any case, I could not bring myself to adopt this way of being. I foresee my soul growing weary. Yes, that may be the norm, but does that make it “right”? With work consuming most of life, is that how I want to live? I’m certainly not the first to ask these questions.

On top of that, there is the societal pressure to establish financial stability and social status. While money and status are extremely real and important concerns that provide for our basic needs and survivability, they could not offer that deep sense of meaning for which I yearn.

Perhaps, I am too big of an idealist, a “naïve” one at that—or maybe all idealists are deemed as “naïve”, especially in Singapore.

I had to make a choice: do I dive into the “real world” or give myself some soul-searching time after graduation? As I spent the final months of my time in university on deep introspection, I was constantly reminded of a common life narrative.

I have personally witnessed, and heard of, so many people overworking themselves for money and status, at a job they barely found meaningful, inevitably burning out, and eventually feeling a profound sense of emptiness from having sacrificed their whole life for something with which they did not truly resonate.

I do not find that prescribed way of living—grounded on the Singaporean culture of hyperproductivity and materialism—remotely enticing. I am sure many of us do not as well. Yet, we succumb anyways because “life happens”.

Nowadays, on social media, you can find several interviews of older folks sharing their biggest regrets in life, one of which is working too much when they were younger.

Here is one that really stuck with me:

“I could’ve travelled more. I’m sorry I let one of the languages I knew when I was younger go. I also really, really regret that I didn’t take advantage of public schools. I could’ve learnt a musical instrument. For whatever reason, I didn’t do it… I think it was because I didn’t think my parents had enough money to buy me an instrument. I didn’t do it and now I regret it desperately. You know, I really wished I had learned to play music because it’s very important to me. I feel like it’s in me, but I don’t know how to express it.”

What struck me about this regret is the sense of not being present. I might not even realize that, by compromising on seemingly trivial things that bring me joy, I’m actually letting go parts of myself that I hold dearly, that define my being.

At the end, I might experience a rude awakening that, sure, I’m still alive, but I don’t feel like I’ve ever existed. I’ve become a hollow shell of my former self.

Some of you might argue that their younger selves were probably just like us. Or that it is only because they have passed their “productive age” that they can say such thing now; money, status, and time no longer hold the same symbolic meaning to them now as those things did when they were younger. You would be right. But I also think it is possible for the younger generation to heed their advice, as difficult as it might be.

Can we only learn through actual suffering? Must we always learn from hindsight?

As a culture that is always rushing towards the future, how do we make sense of the following advice that also struck me:

“Don’t continuously look at building things for your old age. Live in your current life because while you’re building for your upcoming life, you’re missing a lot of things here.”

I had to decide between conformity or choosing my own path, which depended on whether I could resist the societal pressure to conform.

Several factors determined such a heavy decision. I shall speak of two that largely informed mine.

The first was privilege. Many would argue that only the rich have the time, space, and resources to even choose what they want to do. Individuality is a luxury.

In such an expensive and pragmatic Singaporean society, it is a privilege to not have money as a priority. Our “dreams” can take a backseat—or, as Singaporeans, do we even dream in the first place? Were we allowed to dream?

The second was self-awareness. Am I able to discern my values from those of society? Can I distinguish the meaning society has ascribed to money and status from my own personal philosophy about those seemingly important things? Are money and status as important as society makes them to be?

At a certain point, some people cannot distinguish themselves from society: they have completely conformed to societal values. Conformity offers a sense of belonging and the comfort of safety.

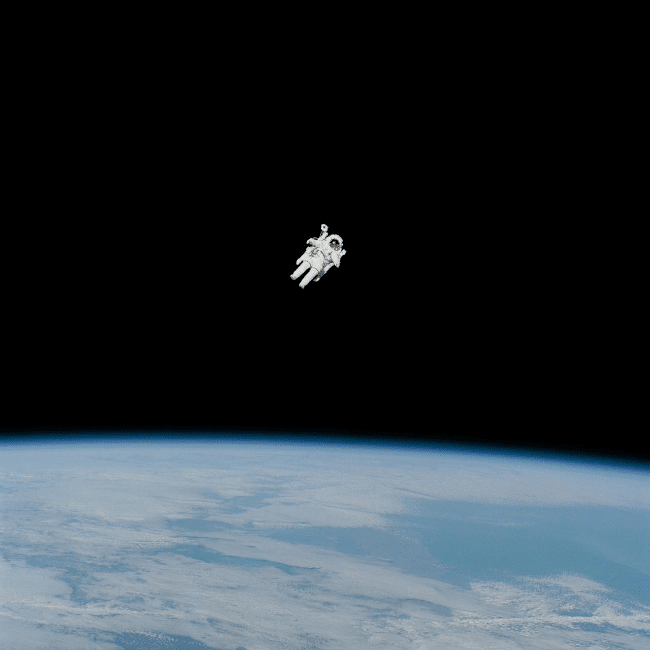

Conversely, while authentic individuals who tread their own path amidst a culture of conformity may experience a profound sense of meaning and fulfilment, they also experience deep alienation and anxiety.

To be clear, there is nothing inherent about authenticity and conformity that makes either one “better” than the other. Our way of living carries the burdens we do not speak of. Who is to dictate one way of living is superior to another? That is almost saying one is better than another at being human, which is absolutely absurd.

For me, right now, given a variety of factors, I have chosen to embrace the risks and anxiety that come with living more authentically.

Eventually, I decided to pursue a master’s in counseling. My family is by no means well-off: my mom is a cashier at a coffee shop drinks stall, and my dad is a security guard.

However, they were extremely supportive of my decision. While I was secretly contemplating postgraduate studies, it was actually my mom who first expressed her support.

They rather I pursue something I truly resonate with instead of settling for a standardized career that would lead to an unfulfilling life.

To them, the most important thing is not money but my contentment. My privilege is not having rich parents but extremely supportive ones.

I also reflected on my values, personality, strengths and weaknesses, and the different possibilities of my future.

I concluded that because I am the type of person who can only excel in what I am genuinely interested in. Paradoxically, the best idealistic but also practical decision was to pursue my interest.

That way, I can maintain sanity while still accruing money to repay my parents. A depressed me, incessantly chasing money and status, would only worry my parents in the long run.

Yet, my pursuit of meaning and individuality did not actually escape the grasp of Singapore’s obsessive hyperproductivity I so adamantly reject. I did not escape the “rat race”, as they say.

Although the master’s program is two years (part-time), I decided to not work and instead use my remaining “free” time to explore material outside the curriculum.

Since I am genuinely interested in the field, it was easy to immerse myself.

My financial expenses—purely funded by my own savings since national service and university—were kept at a minimal by cooking my lunches every day, mostly spending on transport to school.

It helped that I am a homebody, and even more so now since my friends are working.

At the time of writing this reflection, I had just completed two trimesters and was beginning the second one-month study break. By that time, I was burnt out from having read so much during the first two trimesters.

I began to lose my initial passion and wonder; I barely read anything during the break and spent my time watching shows. While I acknowledged that my burnout was a sign to rest, I could not help but feel a gnawing restlessness.

The more shows I watch, the more anxious and ashamed I felt about being “unproductive,” the more I avoid the “real” and “productive” work I felt I was “supposed” to do, the more shows I watch to repress my anxiety and shame, and the cycle goes on. It felt dangerous to keep still: even engaging “unproductive” activities felt safer than doing nothing.

I thought by not chasing money, I had already divorced myself from notions of productivity so intimately tied to money. Evidently, I was wrong for holding so tightly onto the false dichotomies of meaning and money, self and society.

Just because I was not chasing money does not mean I have escaped from the competition of productivity, which is the underlying mechanism of chasing money.

If my peers are more productive financially, I felt like I should be more productive in creating an existentially meaningful life. So that I am on equal standings—so that I am enough.

My experience reminded me of what Nietzsche said:

“We labor at our daily work more ardently and thoughtlessly than is necessary to sustain our life because it is even more necessary not to have leisure to stop and think. Haste is universal because everyone is on flight from himself.”

At some point, we are busy for the sake of being busy. Efficiency and speed are virtues. We rather do anything than do nothing. There is shame in resting. In the end, what are we truly working for?

As Nietzsche observed, my constant activity—productive or not—was really an attempt to run from myself. I was running from the crushing weight of the responsibility to continuously forge my own path. I was running away from that insidious voice within, whispering, “You should be doing more. If not, you will not be enough”. I was running from my inadequacies. Keeping still felt dangerous because I would have to finally face my conscience, and perhaps, admit that I am too “weak” to live an authentic life.

In this journey of treading my own path, I am also constantly reminded of a specific chapter in Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, “On the Way of the Creator.” Zarathustra said:

“Lonely one, you are going the way to yourself. And your way leads past yourself and your seven devils. You will be a heretic to yourself and a witch and soothsayer and fool and doubter and unholy one and a villain. You must wish to consume yourself in your own flame: how could you wish to become new unless you had first become ashes?”

Without fail, whenever I share with someone that I am pursuing a part-time degree, they would ask if I am concurrently working. And without fail, instinctively, I would feel within me a defensive need to justify my choices.

My response usually begins with, “I decided to spend all my time studying so that I can properly absorb the content. I think it is especially important as a counsellor.”

That response would have sufficed. In retrospect, everyone seemed genuinely convinced.

But immediately after, I would always squeeze in a burst of justifications like “I know I am selfish for being a financial burden to my parents for another two years”; “I feel guilty for doing so”; “I am extremely frugal to be less of a burden to my parents”; and “I made this sacrifice because I think pursuing meaning and authenticity is more important than money”.

On the surface, I was afraid others would think I am “unproductive” or “lagging behind”. Hence, I overcompensated by being the first to acknowledge and rationalize my “inadequacies” before they can do so in their mind.

Subconsciously, I thought by being one step ahead in this way, I can compensate for my “lagging behind,” and finally keep pace with others.

But in actuality, I was the one who believed those things about myself. I was the one who needed convincing. The insidious voice within me was not of society but of my own “seven devils” and “doubter.” I am my worst enemy.

Coming to terms with my self-doubts destroyed the delusions I had about who I thought I am. I was not as “noble” as I thought I was for pursuing meaning, nor was this “meaning” as pure as I portrayed it to be.

Indeed, I was a “fool” and a “villain”. Now, I have turned into ashes—awaiting to be built up and burnt down again.

However, despite that whole rollercoaster of self-deceptions and running-away, one thing is certain: I have never regretted my decision thus far.

Sure, I have my doubts. I feel lonely and scared. But my intuition—the soothsayer—predicts, this path I have forged for, and by, myself will be worth it.

Lest I grow mindless and complacent, my soul—the heretic—will not only challenge the norms of the world, but will ceaselessly put my own beliefs and values to the test. And lest I lose sight of myself, I trust in the wisdom that draws me back to my true course.

In the “real world,” we are objectively filtered through the lens of value: better/worse, useful/liability, productive/unproductive, competent/incompetent. But I know we are so much more. We have to be.

But what do I know? Maybe the “real world” is “right”: I am just a “naïve kid” who is too “idealistic.” But who knows? Maybe that is my saving grace. Instead of making the “right” choice, I think I will pick a “mistake” I can live with.

About the Author

Hello, I’m Gary: A recent Anthropology graduate from Yale-NUS College, and an incoming student pursuing a Masters in Counselling. If I were to describe myself in a sentence — which is impossible, but I’ll try nonetheless — I’m currently someone who’s in a perpetual existential mood!

I invite you to join me on my journey of writing to make sense of that mood, myself, and this crazy, complex world. I’m not following a fixed structure, so I don’t know what I would come out of this conviction — I guess we can only find out as I write!