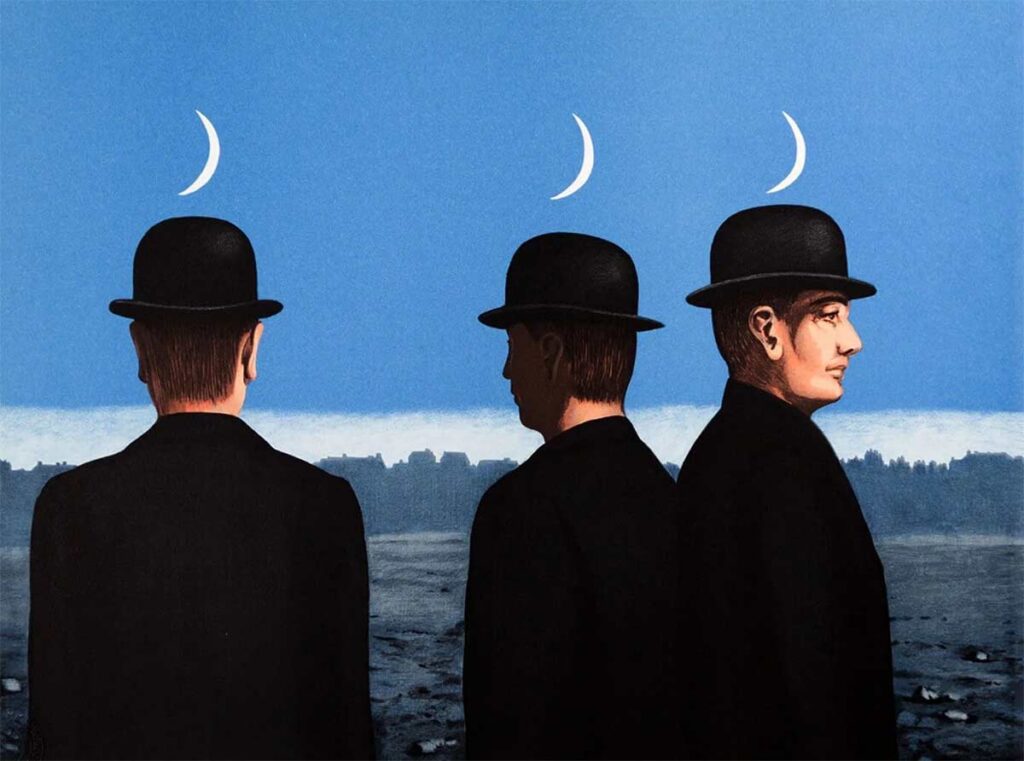

Friends at a Distance: Social Strangers, Existential Companions

What does it mean to be a friend, much less a good friend? Not that I’m not surrounded by good friends, but I’ve noticed my incapacity to be truly vulnerable with them, even the closest ones. It’s hard to reveal my inner concerns without being prompted first. In this sense, my unsatisfied cravings for intimacy […]

We Are Called to be Responsible For Our Voices.

I’m so glad this CNA commentary came up. It says something about our voices. As we find our voices as Asians, we also need to think about taking responsibility for our voices. Rightfully pointed out by Jonathan Kuek, there is “a fine line between trolling and calling someone out.” Existentialism challenges us to confront the […]

We Can Have Many Different Ways of Living

Tan Kheng Hua was a familiar face in my younger years and for many Singaporean millennials. I remember growing up and watching her on TV in Masters of the Sea and Phua Chu Kang. She was also in some of my all-time favourite productions by Wild Rice and TheatreWorks: Animal Farm, The Eleanor Wong Trilogy: […]

Filial Piety and Obligation

The other questions I have long struggled with are what is love and what is obligation? To put it simply and dichotomously, it seems that the West values love while the East values obligation. I’ve conducted my own informal research in this matter by bringing up the example of Jack and Rose. You know them! […]

Filial Piety and Love

Having spent about half of my life in both the US and various parts of Asia, I endeavor to incorporate the best of the East and the West. From the East, I experience deeply that “blood is thicker than water.” I learned about family pride and honor. I recall the pride and relief I felt […]

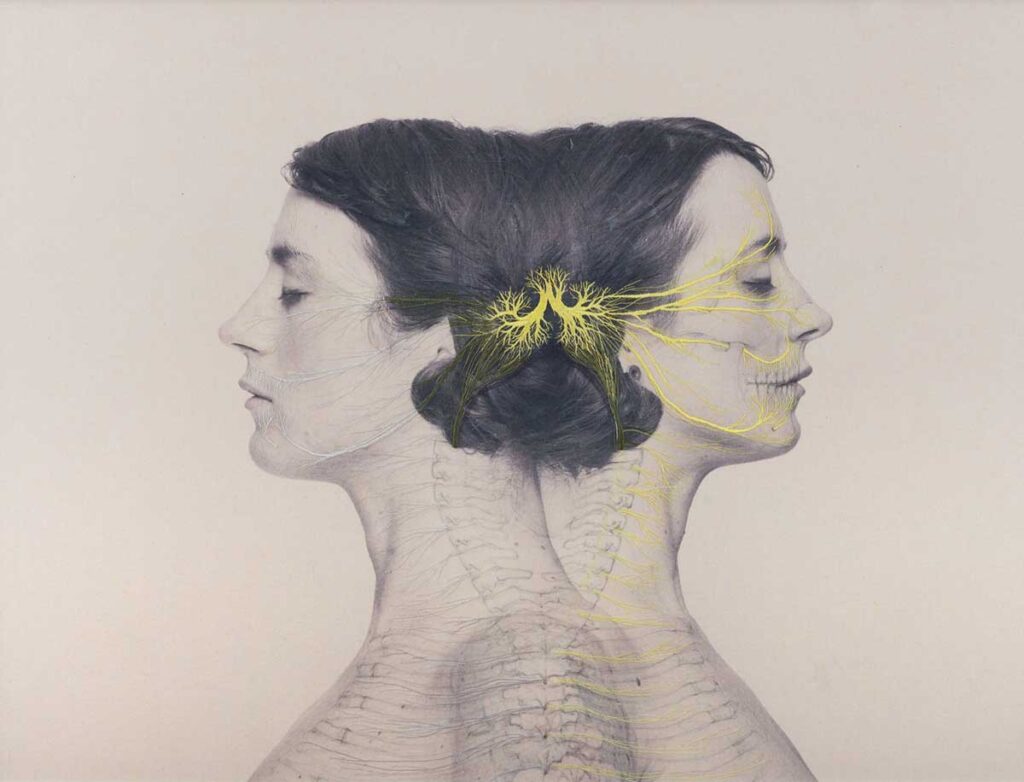

Becoming Human: The Ceaseless Pursuit of Authenticity

The Singaporean Student: Robot or Human? I recall vividly—I was 18, when I experienced a meltdown while studying alone in a classroom for my International Baccalaureate exam. I desperately held back my tears, mind dizzy, short of breath, and asked myself: “Why the f*** am I doing this to myself?” That moment was the height […]