The Singaporean Student: Robot or Human?

I recall vividly—I was 18, when I experienced a meltdown while studying alone in a classroom for my International Baccalaureate exam. I desperately held back my tears, mind dizzy, short of breath, and asked myself: “Why the f*** am I doing this to myself?”

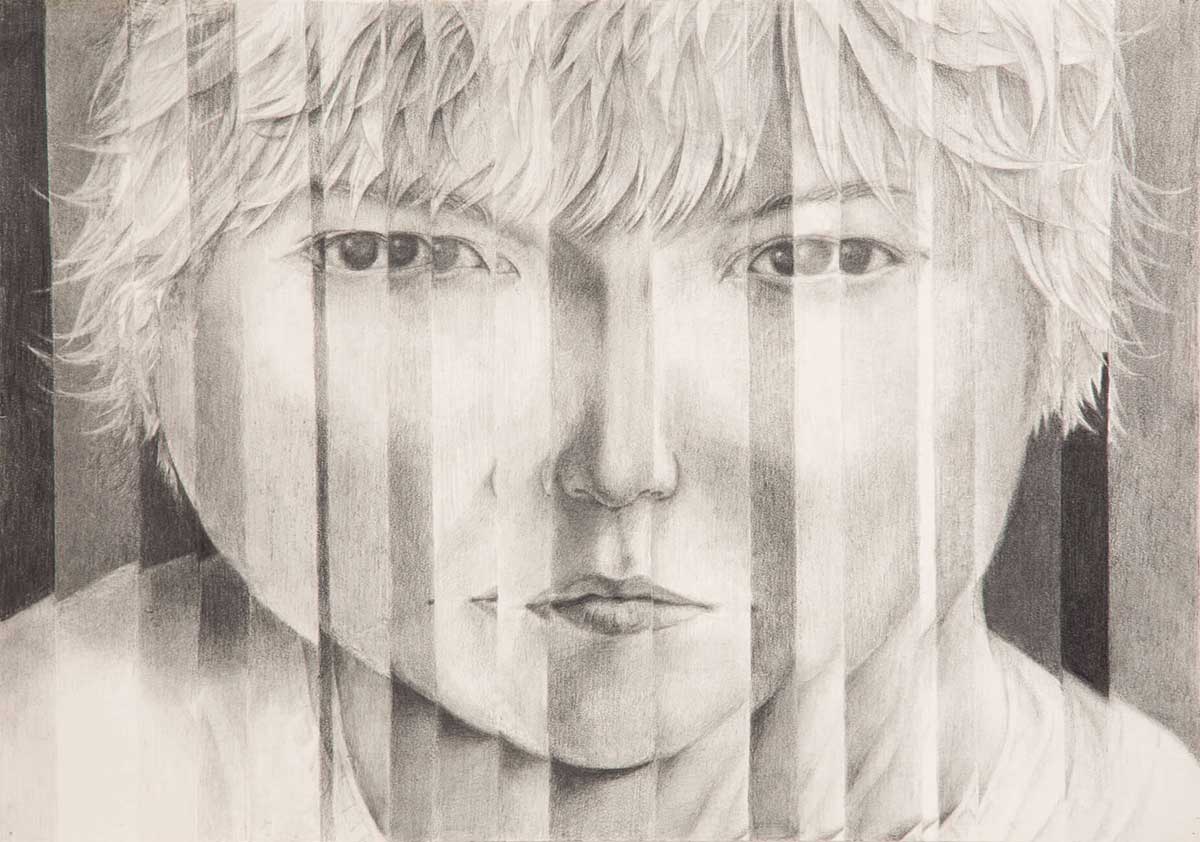

That moment was the height of my burn-out and disillusionment with Singapore’s education system, and more broadly, the standard Singaporean life trajectory. I recognize I was in an iron cage, a mere cog in the machinery that is the Economy. But I am no damn machine: how else can you explain this quivering heart? Yet, I was overwhelmed by momentum as I continued studying like a machine in overdrive—automatic and mindless. I couldn’t let my efforts go to waste, but something’s got to change.

This is not what I truly want. This is not who I am. All I felt was an inarticulable frustration. Would university education still prioritize the meaninglessness of rote memorization and the over-emphasis on grades? What would I become if I continue down this path?

I instinctively knew what I would feel: regret. I was terrified because buried deep within me was a potential longing to be nurtured. My being ached to be articulated. I yearned to be heard and seen. I desired to be my own person. I was on a mission to seek authenticity.

Like many others who were forced to tread this path, I was sick of being evaluated primarily by an exam transcript. I know I am so much more than a letter grade. Yet, my personal growth and worth as a human being are reduced to an abstract economic potential to be exploited by the state, to boost the country’s economy. Within this abstract structure of production line, I am merely a faceless but productive (what a great consolation) member of the workforce. How was I to find authenticity in this inauthentic world?

Bad Faith: The Subtle Art of Self-Deception and Betrayal

As luck would have it, I found out about Yale-NUS College (YNC), the first liberal arts college in Asia and Singapore. In many ways, YNC was radically different from Singapore’s education system. The YNC common curriculum offered the flexibility to explore a range of core modules—philosophy, natural sciences, social theory, coding, literature—and major electives from a wider selection of disciplines.

Most important to me, the curriculum only required students to declare their major at the end of their second year, which gave me time to actually explore and experience what I truly enjoy learning. The western liberal culture encouraged students to express their idiosyncratic selves. Furthermore, the student body is half local and half international, a social environment I believe would encourage and force me to step out of my comfort zone.

During my first year in YNC, I reflected on how “YNC assesses students not just through their academic prowess, but also their character, passion, dreams, and most importantly, as humans, not robots churning out perfect grades.”

However, even though I received an offer from YNC, there were countless times I almost backed out, and instead chose other local universities.

My anxiety overwhelmed me with second-guesses: Is this truly what I want? Am I trying to be someone I’m not?

My fundamental worry was I’m biting off more than I could chew; maybe I was too naïve to believe such a fantasy. I tried to convince myself I would be more at ease in a purely local environment because, after all, that’s where I truly belong, right? Jean-Paul Sartre (1943) would argue my cop out as an instance of bad faith, where one engages in self-deception, pretending to be other than one is, thereby reducing one’s vast possibilities to one singular reality that one pretends to be absolute.

To be in bad faith is to subconsciously avoid self-confrontation and to limit one’s potentialities. Indeed, I attempted to lie myself out of a commitment that may trigger, I surmised, the most anxiety I would ever experience. But it was also a commitment that would catalyse a radical growth in myself. Who even is the real me? Who should I listen to?

Honestly, I didn’t know. But one thing was certain: I had a strong intuition that the right thing to do was to choose YNC. Otherwise, I instinctively knew in my gut I would feel immense regret and guilt. I would’ve betrayed myself. Thinking back, the dilemma of choosing between YNC and other local universities felt like I was putting my life on the line. Given the frustration I felt, this seemingly straightforward decision became much, much bigger for a kid whose wish was to be “human.”

Freedom and the (Dis)comforts of Authenticity

In my first year, YNC truly felt like a utopia. For the first time, I, and I’m sure many others as well, had a space to breathe and unabashedly be ourselves. As with any place, its culture (e.g. YNC’s liberalism) demands an extent of conformity. But, by and large, YNC embraced its students’ idiosyncrasies and celebrated their diversity. Regardless, my pursuit of authenticity was anything but smooth.

The freedom to explore brought more disorientation than clarity. Before finally declaring anthropology as my major, I explored psychology, urban studies, computer science, environmental studies, and philosophy. As I experienced each discipline, I hoped at every exploration that this will be my final one.

As the uncertainty and anxiety were often too overwhelming, there was almost a silent desperation to merely settle on a major based on superficial practicalities (e.g. computer science majors are generally paid well), especially given how my friends had all figured out their majors.

I felt left behind and inferior. What if I don’t become who I thought I’m capable of becoming?

Without a stable identity marker, I almost couldn’t recognise myself. But as with my decision with YNC, I knew it was against my conscience to settle for a major with which my being did not truly resonate. This wasn’t any simple decision: my choice could make or break my life. I resisted the impulse to settle and continued with my exploration and pursuit of authenticity.

The funny thing was I did not attend any anthropology modules before declaring it as my major. In fact, I first declared environmental studies as my major, and at the last minute, switched to anthropology. While I resonated most with the nature and philosophy of anthropology, my initial aversion towards anthropology was its emphasis on reading, writing, and speaking, which I was at best mediocre at.

Rather than listen to my heart, I cared too much about how I may be perceived by others, but most critically, by myself. I feared the amount of work I had to put in.

Most poignantly, considering how so many intellectual YNC students wrote and spoke so exceptionally well, I feared that crippling sense of inferiority. I didn’t believe in myself—I didn’t think I was good enough. And I almost walked away to protect my ego and pride. Once again, I tried to lie myself out of an opportunity for growth.

I avoided my conscience, and almost settled for something I did not truly want. Part of pursuing authenticity is understanding how the authentic self isn’t always who you already are, but more often than not, it’s also who you are trying to be—the self you have not yet become. Authenticity, then, is a state of becoming, which entails taking a leap of faith away from comfort and towards anxiety and uncertainty. Authenticity isn’t always comfortable.

On hindsight, of course choosing YNC has inspired profound personal growth for which I cannot be thankful enough. Philosophically, considering the immense growth of selfhood and the meaning from experiencing such growth, I would choose YNC all over again. However, experientially, I do not wish to go through such a growth again.

I was so, so anxious every day because class participation was most encouraged, as well as the pressure to sound intellectual. I dreaded going to classes; I was always listless because I dissociate as a coping mechanism, which meant I was never fully present during class.

My heart raced in anticipation before and during my one-minute participation, rehearsing obsessively what to say. I couldn’t focus on what my classmates were sharing. Once my participation was over, my body would shut down from mental and physical exhaustion, unable to focus any more. I’ve always wished I wasn’t so neurotic. I never hated myself for it, but I’ve always subconsciously worked to rid of it.

I felt that this neurotic and inferior self is not the real me.

But part of those experiences of anxiety is understanding how authenticity is also accepting who you are, especially parts you do not like, and from that acceptance recognize how those “bad” parts are not intrinsically bad. Authenticity is acknowledging those “bad” parts’ potential for growth, not its “badness.” Authenticity is accepting yourself in whole.

Me “Against” The World: The Authentic and Relational Self

Now, while I’m insecure, I’m also ironically self-assured. I casually read philosophies, such as existentialism and stoicism, to arm myself with perspectives to counter the superficialities of life, like caring too much about what unimportant people think of me. I turn inwards, constantly reflecting on my own values, actions, and what is most meaningful to me.

It is amazing to be able to withstand the forces of conformity, especially when collective values contradict personal ones. Such an unwavering authenticity and sense of self requires much discipline, trust, and reflection to understand not just yourself but the multiple intersecting worlds in which you exist. Such an unwavering self reminds me of a quote by Albert Camus:

“In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer.”

Indeed, being alone doesn’t necessarily mean feeling lonely. In fact, being in bad company, however big, makes for a lonelier time. However, as human beings, we are fundamentally relational. I speak from experience, as someone who valorizes his own solitude and sense of self, sometimes to the point of cynicism. But, inevitably, I will feel lonely. I speak only for myself, that my summer is undoubtedly far from invincible.

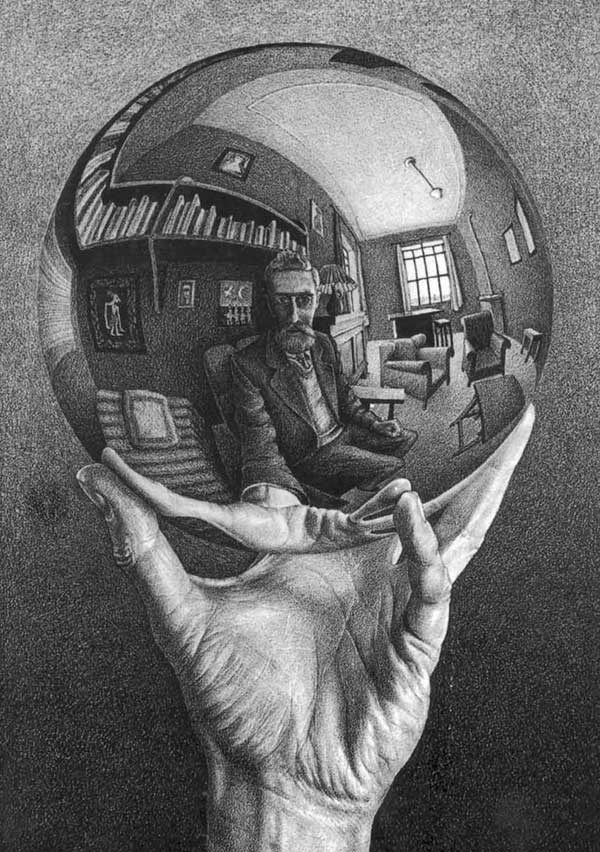

Some of my happiest and most meaningful moments are undeniably those spent with people. In archeology, authenticity refers to something “original,” such as artifacts displayed in a museum or sold during an auction. To establish authenticity requires authenticators, those who authenticate. This suggests that authenticity requires an externality to determine whether you are real or a counterfeit, which contradicts Camus.

I borrow this analogy to make the following claim: we all need our own authenticators—but we should not bend our knees to anybody just because you seek validation. Know yourself first. Then, find worthy authenticators. With your own heat withstand the unflinching, stinging winter that is the inauthentic crowd until you find people willing to embrace your summer, people who find your heat not too overbearing nor not hot enough, but just right—warm and cozy.

I am lucky enough to have found my own authenticators, but let me tell you it was not an easy journey. I am still learning how to be a relational being; I still doubt my own authenticators at times for not capturing me in totality. However, the authentic self need not be a constant, uniform self.

It is not possible to capture one’s being in totality for you are constantly changing. So, instead of resenting my authenticators, I remind myself of how lucky I am that they continue to stay by my side.

At the beginning of my desperate pursuit of authenticity, I was chasing after an ideal image, someone I must become. I’ve since learnt that authenticity is not some sort of essence that you will one day fully possess. We usually take a “human being” as a noun or a static state. However, “being” is a verb, which means we are constantly becoming human through our daily doings. Viewed this way, we never really are, but we are becoming.

If we are constantly becoming and emerging, it also means the horizon of our potential grows in tandem. Authenticity, then, is not a complete state that which we can possibly reach. Yes, authenticity may still be staying true to your values and who you are. But, perhaps, in a more existential sense that speaks to the core of your being and existence, the nature of authenticity is something processual, a doing, and being human means fulfilling your potential. More precisely, perhaps, it is the very striving towards an ever elusive fulfilment that makes you an authentic human being.

Ultimately, I am still wrestling with the idea of authenticity. As I graduate from university, and transition into the “real” world, I will continue thinking, doing, and relating, in hopes of fulfilling my 18-year-old self’s humble dream that was an ironic impossibility—being an authentic human.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1943. Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology. New York: Washington Square Press.

About the Author

Hello, I’m Gary: A recent Anthropology graduate from Yale-NUS College, and an incoming student pursuing a Masters in Counselling. If I were to describe myself in a sentence — which is impossible, but I’ll try nonetheless — I’m currently someone who’s in a perpetual existential mood!

I invite you to join me on my journey of writing to make sense of that mood, myself, and this crazy, complex world. I’m not following a fixed structure, so I don’t know what I would come out of this conviction — I guess we can only find out as I write!