What does it mean to be a friend, much less a good friend?

Not that I’m not surrounded by good friends, but I’ve noticed my incapacity to be truly vulnerable with them, even the closest ones. It’s hard to reveal my inner concerns without being prompted first. In this sense, my unsatisfied cravings for intimacy are largely of my doings. My isolating myself causes others to isolate from me.

Looking back, I was never really there for my friends during crises. More accurately, I was never called, and I, too, have never called my friends during my crises. The smoothness of my friendships was partially, and possibly, a delusion of closeness. My supposed best friend of 18 years, Kai, whom I went to primary and secondary school with, share a peculiar friendship. It’s one of those friendships that’s low-maintenance, perhaps, too suspiciously low such that one might question whether we’re even friends. Yet, it’s ironically robust.

We’ve never talked about “serious” things. And unsurprisingly so—we were young and naive, too focused on having fun to even think about who were and what we were living for. After graduating from secondary school, we met up once in a while. Kai spoke most of the time, not because he didn’t care about me, but because I was afraid of showing him who I’d become. I think he could sense that. Knowing how I’ve always been more on the quiet side, he eased my discomfort by filling up the silence. I was thankful, but I left every meet-up with an existential regret: If only I had the courage to connect with him deeply.

It was only after my university graduation that we finally met for dinner after a whole year of absence, and had our first ever “serious” talk.

In a world governed by superficialities, I’ve always feared expressing my existential concerns. I was afraid Kai would find me too serious or pretentious. Would he prefer to talk about the technicalities of his job or his hobbies? I wouldn’t know where to even begin asking: His social world has become too foreign to me. I was, instead, most interested in how he was doing existentially. Would he be comfortable sharing his existential vulnerabilities given how long we’ve been apart? With the increasing distance between us, the only way I believed could maintain our friendship was to deepen our existential connection.

I took the courage and decided to show him the self I’ve become. For the first time, we talked deeply about what meanings we wish to create, our relationship with our families, our selfhood, and our friendship both back in the day and what it is now. As he shared his stories, I was viscerally struck by how un-relational I’ve been. I found out he was once depressed and contemplated suicide because of a heartbreak. I found out when we were in Secondary 1, I allegedly told him that I wished I could be as happy as him, and he went home and cried because he couldn’t be any further from the happy person I mistook him to be. I found out he wasn’t that confident and charismatic guy I sincerely thought could take on the world all on his own, that he actually feared being alone and craved the company and comfort of other humans.

As heartened and connected as I felt during our conversation, I was awash with guilt.

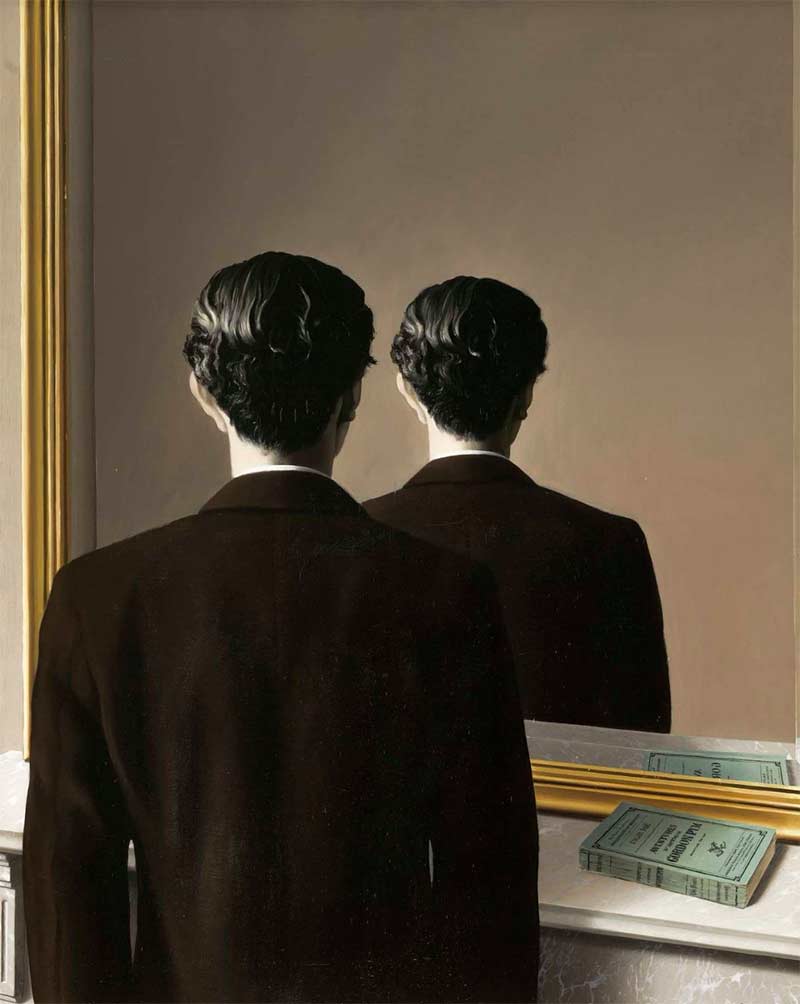

I kept asking myself: Why am I only now finding out about these things? Who even was this “Kai” I thought I knew? Who even was the “I” who thought he knew his friend? How lonely must he have felt? Was he ever on the verge of texting or calling me for help? Why didn’t he? From the start, was I never someone he thought he could turn to in times of despair?

A connection and a gulf in our friendship were in paradoxical formation. I experienced simultaneously my adolescence and adulthood, my past and my present, as they clumsily shifted in tandem amidst my overwhelming and confusing emotions, to negotiate some sort of reconciliation so that I could figure out how to be in the future.

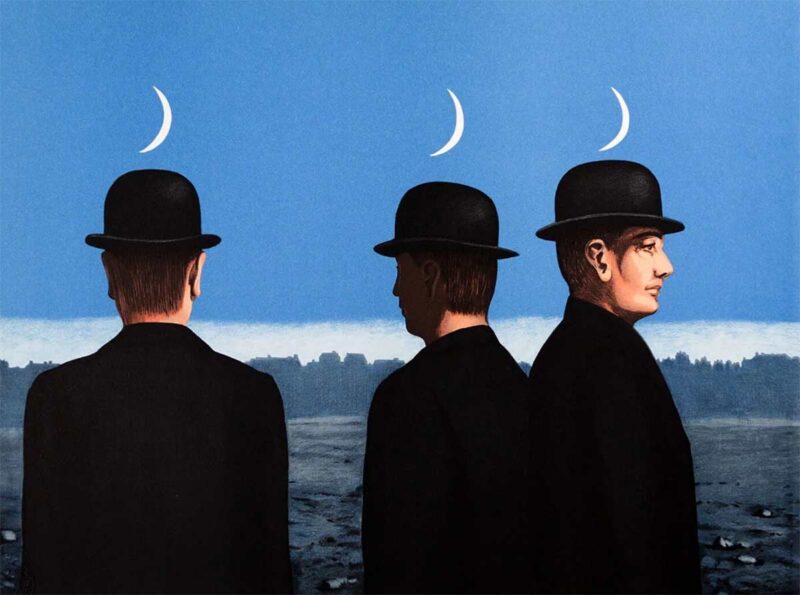

Was I to blame any of us for isolating ourselves? Is relationality primarily physical proximity? How do I explain my deep sense of trust in Kai despite the distance between us? Spinelli (2007) suggests isolation is not diametrically opposed to relationality, but isolation is one form of paradoxical expression of relationality. Isolation is still a way of relating to someone. Ultimately, Kai and I made decisions that relationally preserve our friendship in our own unique and seemingly un-relational way. Some would describe this as what adult friendships are quintessentially like—everyone is living their life, one that is as vivid as yours, and everyone seems to be diverging, ever-receding into the distant horizon. Without constant effort, adult friendships would eventually drift apart. Yet, despite acknowledging the increasing distance, I don’t doubt the strength of our bond.

We might not occupy the same social world of interests and careers, but we have very similar attitudes, characters, and philosophies in living and approaching the world. Between us, there might be a vast social chasm, but we’re existentially intertwined—a connection much more profound, and hence, robust, than any other forms of social connection.

During my times of crisis, I always question whether I truly needed help. Is my situation so dire that I have to call Kai? I’ve never wondered why, but for the longest time, calling Kai for help has always been my last resort. As I reflect upon the nature of our friendship after that dinner, it became clearer, at least to me, that my isolation from him was not because of the fading strength of our friendship, but because of my having witnessed his resilience amidst adversities and how fiercely he confronts life. Until I’ve attempted to live as fiercely as Kai, and to once again uphold our shared principles of which I’ve momentarily lost sight, I will not call him for help. As always, things worked out. My “isolation” is my accountability to, and reverence for, our shared attitude and principles towards living. In that sense, we were never as distant as I thought. Kai has always been a part of me—living life together.

After every meet-up, we both always text each other something along the lines of, “Eh bro, I know I’m not really present in your life, but know that I’m always here for you and just a phone call away when shit hits the fan.” Is this an empty promise?

I can say wholeheartedly that it’s not. I mean every word I say. I’m sure he does, too. That’s how much I trust him.

It has been seven months since we last met for dinner. We haven’t talked since. It seems like nothing has changed; we went our separate ways, like always. But something has indeed changed, and profoundly so: We’ve finally validated each other’s new existence, as well as our past ones that almost drifted into oblivion. I don’t want to think about what would’ve happened if we did not meet that night. All I can say is that I’m so glad I had the courage to finally show him who I am and to ask him who he is.

I’m not expecting our phones to start ringing more often. It’s okay if our phones remain silent. What matters more to me is that I know when the phone rings, we will drop everything and rush to each other’s side when shit truly hits the fan.

We may be passing social strangers—but we’re lifetime existential companions.

Spinelli, E. (2007). Practising existential psychotherapy: the relational world. Sage.

About the Author

Hello, I’m Gary: A recent Anthropology graduate from Yale-NUS College, and an incoming student pursuing a Masters in Counselling. If I were to describe myself in a sentence — which is impossible, but I’ll try nonetheless — I’m currently someone who’s in a perpetual existential mood!

I invite you to join me on my journey of writing to make sense of that mood, myself, and this crazy, complex world. I’m not following a fixed structure, so I don’t know what I would come out of this conviction — I guess we can only find out as I write!