Being positioned as different.

I am a psychologist and I work on a doctoral programme in the UK. I have found the world to be far more complex than most psychological theorists suggest, and that is why I have taken up an approach which we refer to as ‘phenomenological.’

Phenomenology is a practice that is employed when providing psychological therapy, and in related research. The programme that I help to run teaches this phenomenological practice, and it offers thereby an advanced approach to knowledge construction.

We require that our students adopt a reflexive stance towards the topics that they research, that they critically review how power can be exercised when varying accounts are promoted.

We ask them to consider what an experience means from a person-centred human perspective.

I am interested to know whether phenomenological practices have a uniquely European quality, or whether something of them will translate into another culture, such as that of South-Asia.

My Formative Years

I recall a formative experience, that I had when I was at school here in the UK. We were studying the French language, along with French culture. I had learned that France is a country just across the sea from the UK, somewhere that people speak another language and generally do things differently.

This was evident to me, as our teacher was French. She spoke with an accent, and she seemed quite strange in her manner. Some of us would imitate her way of speaking. In our understanding we knew her to be different, and she was thereby a source of interest and sometimes amusement. Perhaps some of us shared a sense of security and belonging, when drawing attention to her difference. Children learn to play the politics of excluding others from their social group.

However, I really liked our French Teacher. I was interested to know how it was that she was different, and what this meant. I gained some understanding of this when the school organised a daytrip to France. I still struggle to make sense of the experience. I discovered that just by travelling a few miles, crossing a boarder into a different country, I too could become ‘foreign’ – in France, I was a foreigner.

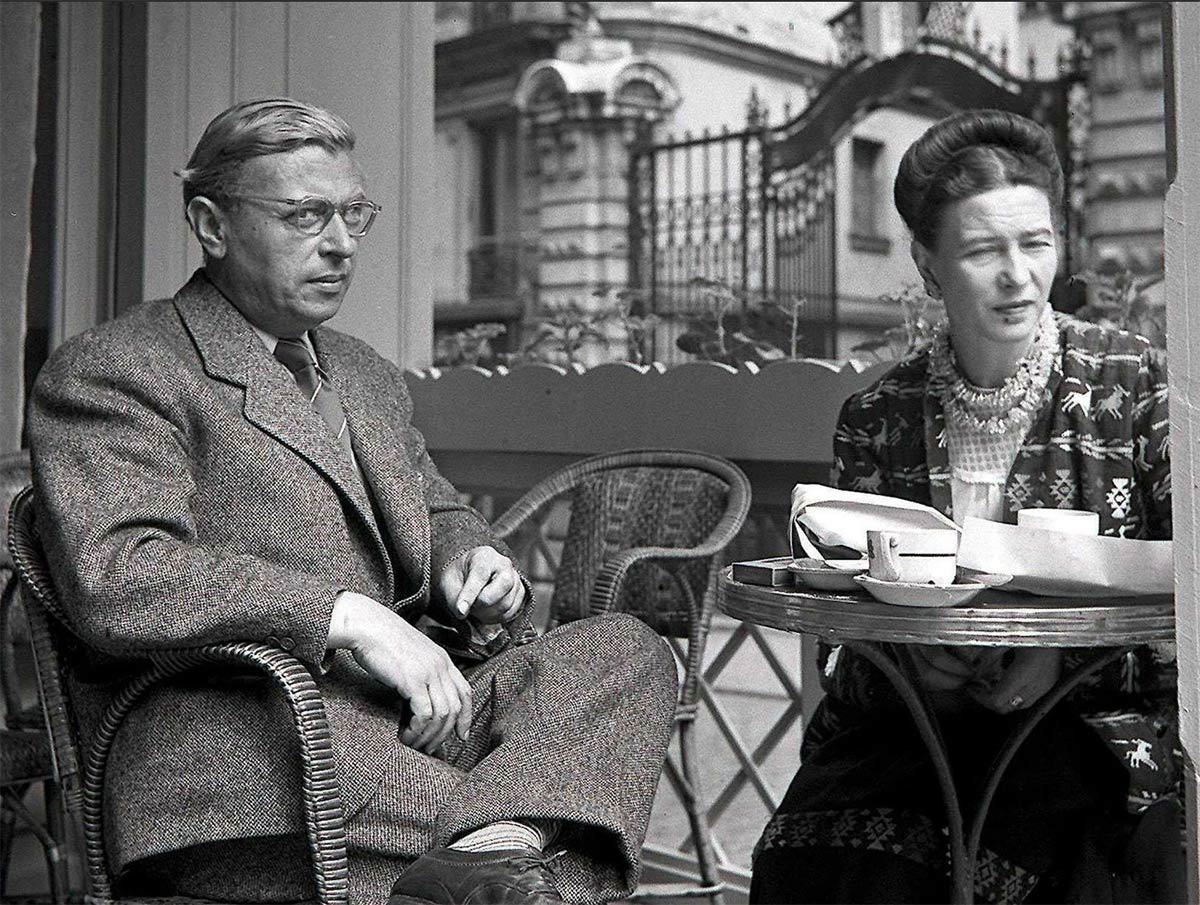

In France, at that time, the philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir were still admired. In their philosophies, they had described how we have no essential essence, and our being can be transformed by the way that others view us (Beauvoir, 1949; Sartre, 1943). Philosophical notions such as ‘the look,’ and ‘othering’ have become extremely important for me in how I understand existence.

These understandings are revealed in a tradition of research and related theory which we call phenomenological exploration. I find this kind of research practice to be helpful. It helps me to unpick paradoxical notions, such as the assumption that ‘foreigners,’ are different.

I am still hearing this way of thinking in talk of ‘asylum seekers,’ ‘immigrants,’ and people from ‘those other countries.’ There is no reference in this talk to anything that is intrinsic to a person’s manner of being. It is where they happen to be in the world that defines their nature.

Is it not paradoxical that where you happen to be can define who you are?

To be more precise, it is not your geographical location that matters so much. In the past, people have decided that an area of the planet’s surface has a given name, with defined boundaries. There are disputes, and names change, boundaries move, but for long periods of time these boundaries exist as conceptual devices. It is within these conceptual systems that we are located.

I recognise that many people do not experience themselves as becoming a foreigner when they leave their country of origin. They are entrenched in their cultural ways of being to such a degree that they carry them with them as the assumed correct way to be. They experience themselves as being for the moment in a country full of foreigners.

I struggle again with the paradox of this.

To be a foreigner you would have to be in the minority, so how can you have a ‘country full of foreigners?’

Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir reviewed each other’s work. They also discussed their ideas with Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Merleau-Ponty wrote about the ambiguity of our subjectivity, taking a phenomenological approach (Merleau-Ponty 1968). He explored the way that we exist in the consciousness of others, how we can come to know ourselves through the experience that others have of us. Edmund Husserl was the founder of phenomenological theory and with the conflicts of war in Europe, it is remarkable that his writings survived. They were moved to a place of safety in Belgium, and they are now in the library of Leuven University. Merleau-Ponty went there to read them, and he took note of comments that Husserl made in his later writings (Bakewell, 2017). The understanding that developed, is that we do not know that we have a cultural way of being, until that is, we encounter someone from a different culture.

Cross-cultural encounters help us broaden our horizons.

If we are open to seeing ourselves as viewed by others, then we have a more complete understanding.

While at the same time, this kind of understanding enables a critique of everyday assumptions.

Often, it seems that is those of us who are caught between cultures, living troubled lives, will find phenomenological practices of value. Perhaps new awareness and insights are more likely to develop where people come up against impossible dilemmas, facing the constrains of ‘limit situations’ (Jaspers, 1932).

Unfortunately, it is difficult to hold theorists up as exemplars, or to idolise them, when they lived flawed lives. Simone de Beauvoir for example opened our awareness of how women have been reduced to a ‘second sex,’ exploited and subjugated. However, with her friend Jean-Paul Sartre, she took advantage of her female students by enticing them into sexual encounters at a very young age (Seymour-Jones, 2009).

As I say above, life is more complicated than most psychologists suggest.

European culture

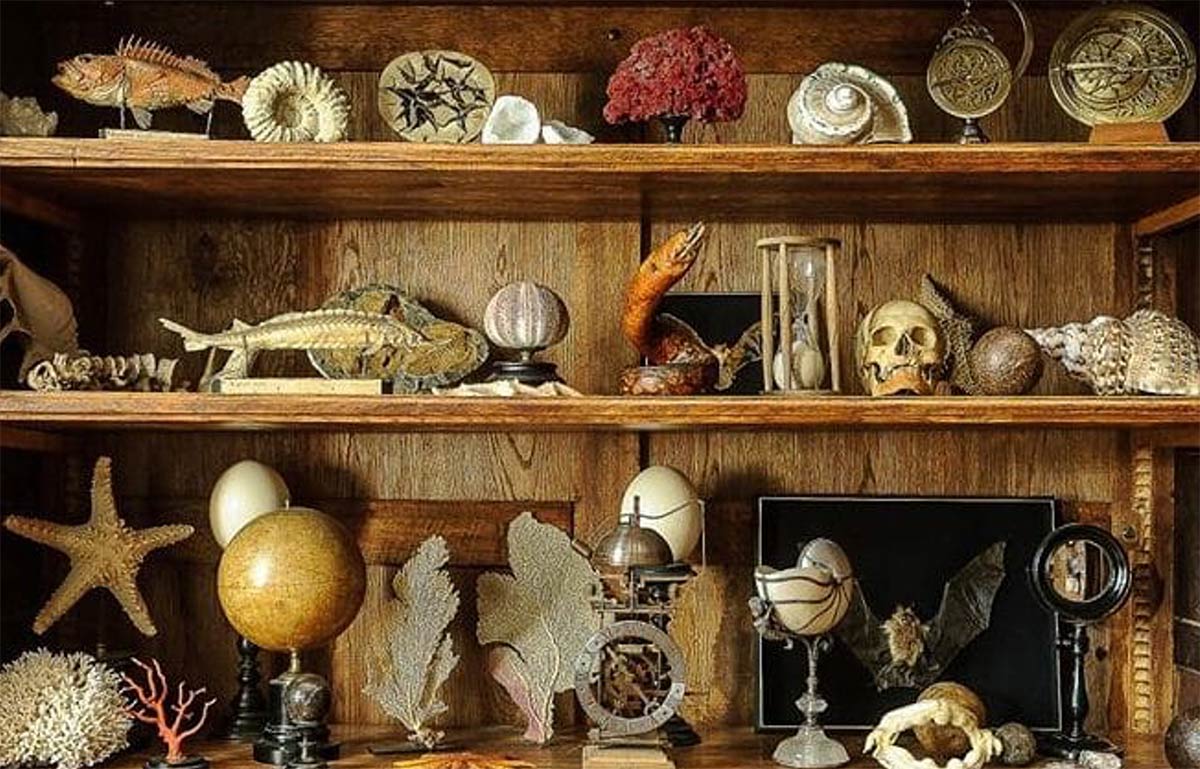

I recall another one of my school trips, when we visited a museum, where we saw a ‘cabinet of curiosities.’ This is a phenomenon which reveals a lot about European culture.

Early examples would include fossils, rock minerals, zoological specimens, along with religious relics and cultural artifacts. These collections evolved in Europe though the adoption of scientific practices. They became more rigorous and systematic.

However, the core theme remained, that the world can be sampled and catalogued in a manner that removes phenomena from the context in which they emerge.

The world is viewed in this approach, not from a given location, but from an imagined ‘view from nowhere’ (Nagel, 1986). It is troubling, that this view happens to have supported the interests of Europeans, mostly rich male Europeans.

As Europeans began to extract short-term profit, robbing the world of its resources, they also viewed people as things to be exploited.

Western psychology has been developed around the tasks of observing measuring, defining, controlling, and managing people (…and marginalising some of them). People, as viewed by these psychologists, have given observable properties. They can be measured and categorised, as belonging to a specific culture, having a given gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and so on.

In this sense, you do not need to cross a national boundary to become a ‘foreigner,’ you just need to be defined psychologically as belonging to a minority group.

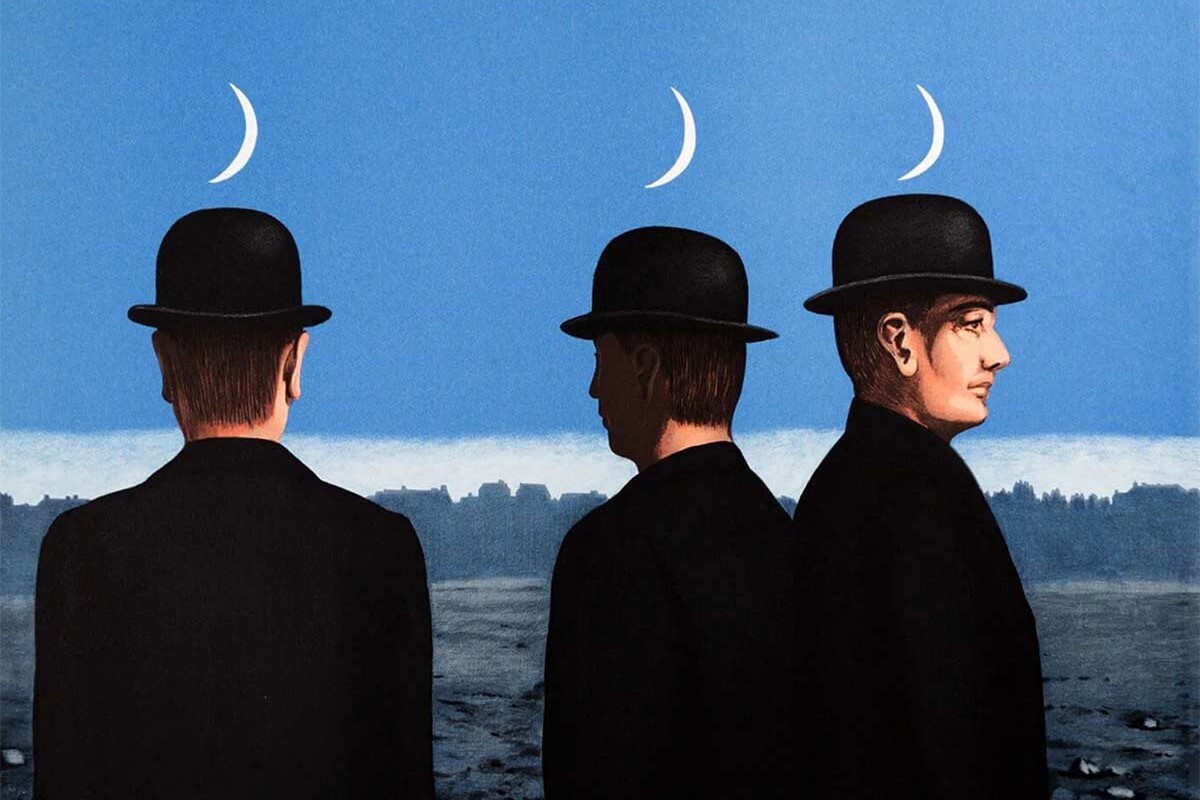

You are positioned as ‘other,’ as not belonging, as strange and different.

Martin Heidegger challenged the idea that things in the world are there, present, ready for us to observe from a dispassionate position (Heidegger, 1927). He was another theorist who made questionable life choices, joining a fascist and racist political movement (Bakewell, 2017). However, his writings help us by explaining how it is that we are already taken up in the world by our concerns.

Things come to hand for us when we want to do something. Their meaning and their value are implicit, revealed by the way we use them. In our everyday ways of being, tools are not things that we stand and contemplate as definable objects. They come to hand in our unthinking routines of getting through the day, doing what everyone else around us is doing. We can lose ourselves in these habits, where the truth of our existence is hidden behind unexamined assumptions.

How we see things and what we do with them are not phenomena that stand out. They do not show up easily as something that we might collect and put on display in a cabinet. They are just the unnoticed fabric of our way of being.

For example, a river in a wooded valley is for some people just the background to their meaningful existence, something that has sustained their ancestors, something which can enabled their future. If that is, it is treated with respect.

Others can only see the potential to cut down trees to sell as lumber, or the possibility of a dam in the river which would generate electricity (Heidegger, 1977). Technologies can, in this manner, make our lived-world uninhabitable.

We will only miss what we had when it is gone.

As psychological therapists, when we work with clients who are very much like us, it is hard to notice our assumptions or understand what we are doing. However, if our client is from a different culture, it will be easier to identify and suspend those assumptions.

We might then realise the mistakes that we are making.

We might notice how it is that people are often imposing assumptions and trying to assimilate others into their own world view.

Globalisation

Human distress is most often viewed in Western cultures as a kind of mental illness.

Western diagnostic systems are like a cabinet of curiosities. A box in which to place each condition, with its label and description.

Psychologists will ask: ‘What is wrong with this person?’, and where should we place them.

They turn to the methods of empirical science to find out how to ‘fix the problem.’ How, that is, to make the person function again as a productive member of our commercial systems. In contrast, phenomenological approaches offer the possibility of understanding what is happening from a human perspective.

Practitioners use reflexivity to explore the reality that each of us is always located somewhere in the world, driven by specific motivations. People are distressed by what is happening in their lives.

People are not something that we can take out of the world and examine as if they were an object.

We are flexible, learning and changing, in response to what happens to tus.

Distress can then be understood as most often the discomfort of being positioned, labelled, controlled, and managed.

Economic forces are unleashed across the world, increasing migrations and cross-cultural encounters. More and more people are confronted with the disturbing reality that their traditional ways of being, in their cultural heritage, are just one way of doing things.

One amongst many.

The blind rationalism of multi-national economic systems threatens to strip each of us of our unique humanness. Western psychology is a part of this when narrow definitions of mental illness are exported and imposed.

In contrast, freedom and choice are core themes in existential theory. As horizons are broadened in cross-cultural awareness, freedoms expand and contract. We become aware of greater possibilities in our options, in the way that we might choose to live. While we might also notice how we are at risk of moving towards a homogenised and narrow commercialism.

In societies where we shame people who are different, everyone is trying to fit in. They are trying to be ‘normal,’ whatever that is. They are following the latest trends, which are usually set by the rich and powerful.

Cultures are appropriated as commodities. The ‘exotic’ has a value, and it becomes something that requires additional payment, in holidays, products, and identity politics. Some people who are economically-disadvantaged must then package their culture and its customs, to sell to foreigners.

Otherness is exploited again, turned into entertainment and amusement.

In phenomenological understanding, we recognise that our knowledge-construction is never free of human interpretations, desires, and intentions. It is essential therefore that these emotional engagements are examined in research processes.

Care can be taken to promote an ethical framework.

With this reflexivity, it is possible to ask: ‘What is it like to have a specific human experience?’, and to use empathy to ease ourselves into an understanding informed by those who are having that experience.

We are not then treating people as things to be measured, fixed or used.

In existential therapies, we are meeting our clients as people, not as objects to treat, fix, change, or process (Buber, 1937).

If we are meeting our clients, then it is likely that both the practitioner and the client will learn and be changed by the encounter.

If existential theory and phenomenological practice are to be taken up in South-Asian culture, then there needs to be a meeting between people who will learn from each other. This is not a psychological therapy which requires that one party is assimilated into the culture of the other.

Both parties will find out about themselves, as much as they will find out about the other.

Phenomenological research attends to the human condition and this will have certain givens across cultures (Yalom, 1980).

We are all embodied, we all interact with other people, we all make choices, and we all die.

Beyond those aspects of existence, which we all share, there are significant cultural differences, which we need to acknowledge, reflect on and respect.

Perhaps there are theorists in Asian culture who have also asked: ‘What is it like to be human?’, theorists who have lived more enlightened lives.

References

- Bakewell, S. (2017). At The Existential Café: Freedom, Being & Apricot Cocktails. Penguin-Random House.

- Beauvoir, S., de (1949). The Second Sex. Trans. H. M. Parshley. Vintage Classics

- Buber, M. (1937). I and Thou (S. Verlag, trans.). Bloomsbury Academic. (2013).

- Heidegger, M. (1927). Being and Time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, trans.). Harper & Row.

- Heidegger, M. (1977). The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays (W. Lovitt, trans.). Harper & Row.

- Jaspers, K. (1932). Philosophy, Vol. 2: Existential Elucidation (E. B. Ashton, trans.). The University of Chicago Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1964). The primacy of perception and its philosophical consequences (Trans. J. M. Edie. In J. M. Edie (Ed.), The Primacy of Perceptions: And Other Essays on Phenomenological Psychology, the Philosophy of Art, History and Politics (pp. 12-42). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The visible and the Invisible (Trans. A. Lingis). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Nagel, T. (1986). The View from Nowhere. Oxford University Press: New York.

- Sartre, J-P. (1943). Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology. (Trans. H. E. Barnes). London: Routledge

- Seymour-Jones, C. (2009). A Dangerous Liaison: A Revelatory New Biography of Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre. New York: Abrams.

- Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. Basic Books.

About the Author

A HCPC and BPS registered Chartered Counselling Psychologist, also a UKCP registered Existential Psychotherapist, and a supervisor and trainer.

With a varied career in the NHS, leading to a specialisation in engaging and supporting socially excluded client groups. Currently teaching doctorial counselling and psychotherapy students at the New School of Psychotherapy and Counselling, London, UK.

Recent Articles About Existential Therapy