Understanding 'Otherness': Phenomenological Practice in Cross-Cultural Encounters

Being positioned as different.

I am a psychologist and I work on a doctoral programme in the UK. I have found the world to be far more complex than most psychological theorists suggest, and that is why I have taken up an approach which we refer to as ‘phenomenological.’

Phenomenology is a practice that is employed when providing psychological therapy, and in related research. The programme that I help to run teaches this phenomenological practice, and it offers thereby an advanced approach to knowledge construction.

We require that our students adopt a reflexive stance towards the topics that they research, that they critically review how power can be exercised when varying accounts are promoted.

We ask them to consider what an experience means from a person-centred human perspective.

I am interested to know whether phenomenological practices have a uniquely European quality, or whether something of them will translate into another culture, such as that of South-Asia.

My Formative Years

I recall a formative experience, that I had when I was at school here in the UK. We were studying the French language, along with French culture. I had learned that France is a country just across the sea from the UK, somewhere that people speak another language and generally do things differently.

This was evident to me, as our teacher was French. She spoke with an accent, and she seemed quite strange in her manner. Some of us would imitate her way of speaking. In our understanding we knew her to be different, and she was thereby a source of interest and sometimes amusement. Perhaps some of us shared a sense of security and belonging, when drawing attention to her difference. Children learn to play the politics of excluding others from their social group.

However, I really liked our French Teacher. I was interested to know how it was that she was different, and what this meant. I gained some understanding of this when the school organised a daytrip to France. I still struggle to make sense of the experience. I discovered that just by travelling a few miles, crossing a boarder into a different country, I too could become ‘foreign’ – in France, I was a foreigner.

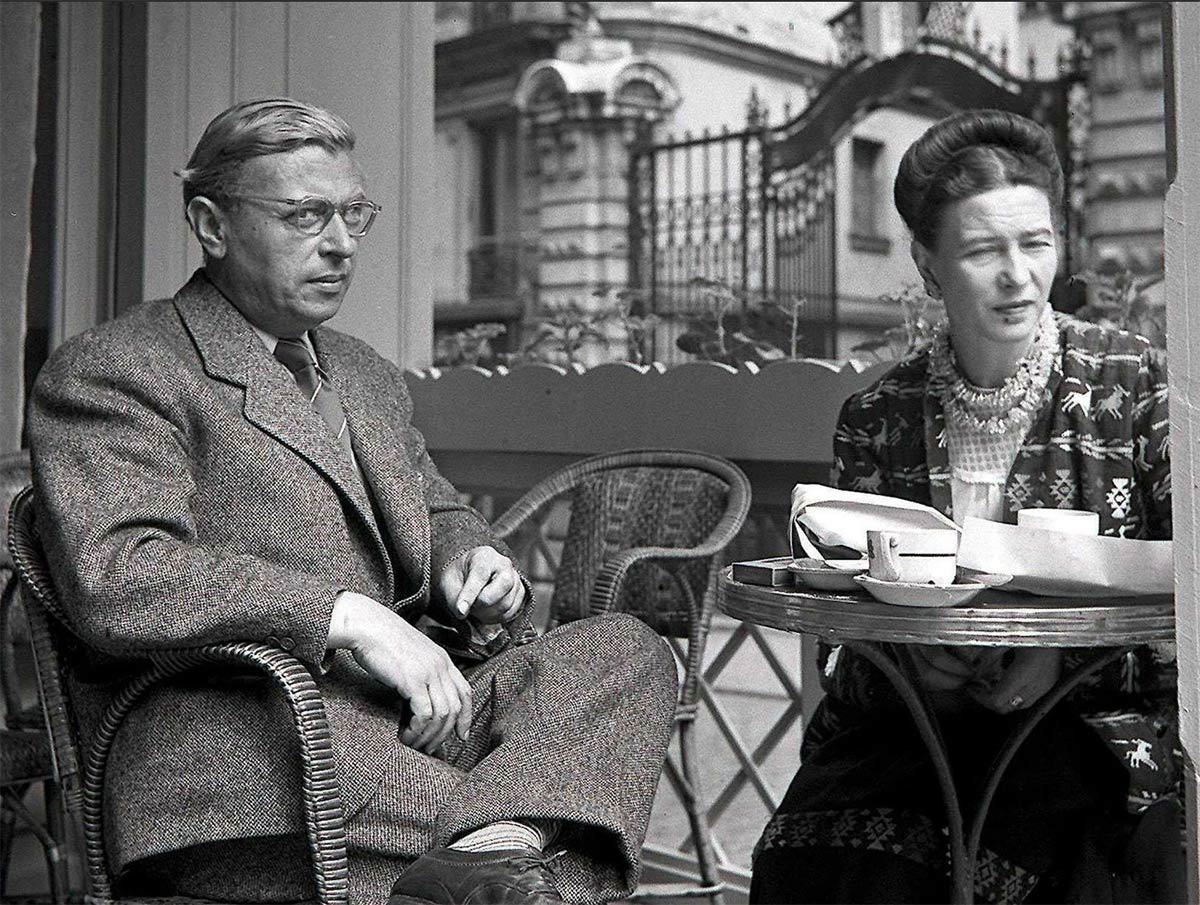

In France, at that time, the philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir were still admired. In their philosophies, they had described how we have no essential essence, and our being can be transformed by the way that others view us (Beauvoir, 1949; Sartre, 1943). Philosophical notions such as ‘the look,’ and ‘othering’ have become extremely important for me in how I understand existence.

These understandings are revealed in a tradition of research and related theory which we call phenomenological exploration. I find this kind of research practice to be helpful. It helps me to unpick paradoxical notions, such as the assumption that ‘foreigners,’ are different.

I am still hearing this way of thinking in talk of ‘asylum seekers,’ ‘immigrants,’ and people from ‘those other countries.’ There is no reference in this talk to anything that is intrinsic to a person’s manner of being. It is where they happen to be in the world that defines their nature.

Is it not paradoxical that where you happen to be can define who you are?

To be more precise, it is not your geographical location that matters so much. In the past, people have decided that an area of the planet’s surface has a given name, with defined boundaries. There are disputes, and names change, boundaries move, but for long periods of time these boundaries exist as conceptual devices. It is within these conceptual systems that we are located.

I recognise that many people do not experience themselves as becoming a foreigner when they leave their country of origin. They are entrenched in their cultural ways of being to such a degree that they carry them with them as the assumed correct way to be. They experience themselves as being for the moment in a country full of foreigners.

I struggle again with the paradox of this.

To be a foreigner you would have to be in the minority, so how can you have a ‘country full of foreigners?’

Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir reviewed each other’s work. They also discussed their ideas with Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Merleau-Ponty wrote about the ambiguity of our subjectivity, taking a phenomenological approach (Merleau-Ponty 1968). He explored the way that we exist in the consciousness of others, how we can come to know ourselves through the experience that others have of us. Edmund Husserl was the founder of phenomenological theory and with the conflicts of war in Europe, it is remarkable that his writings survived. They were moved to a place of safety in Belgium, and they are now in the library of Leuven University. Merleau-Ponty went there to read them, and he took note of comments that Husserl made in his later writings (Bakewell, 2017). The understanding that developed, is that we do not know that we have a cultural way of being, until that is, we encounter someone from a different culture.

Cross-cultural encounters help us broaden our horizons.

If we are open to seeing ourselves as viewed by others, then we have a more complete understanding.

While at the same time, this kind of understanding enables a critique of everyday assumptions.

Often, it seems that is those of us who are caught between cultures, living troubled lives, will find phenomenological practices of value. Perhaps new awareness and insights are more likely to develop where people come up against impossible dilemmas, facing the constrains of ‘limit situations’ (Jaspers, 1932).

Unfortunately, it is difficult to hold theorists up as exemplars, or to idolise them, when they lived flawed lives. Simone de Beauvoir for example opened our awareness of how women have been reduced to a ‘second sex,’ exploited and subjugated. However, with her friend Jean-Paul Sartre, she took advantage of her female students by enticing them into sexual encounters at a very young age (Seymour-Jones, 2009).

As I say above, life is more complicated than most psychologists suggest.

European culture

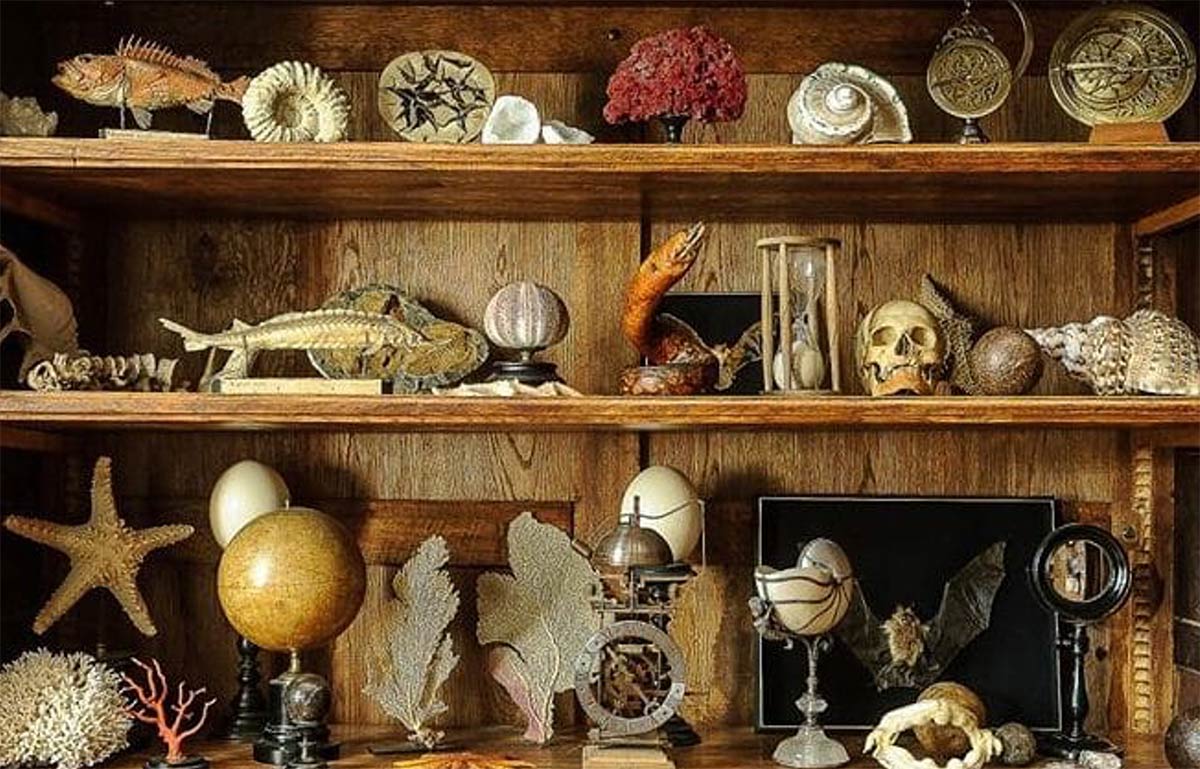

I recall another one of my school trips, when we visited a museum, where we saw a ‘cabinet of curiosities.’ This is a phenomenon which reveals a lot about European culture.

Early examples would include fossils, rock minerals, zoological specimens, along with religious relics and cultural artifacts. These collections evolved in Europe though the adoption of scientific practices. They became more rigorous and systematic.

However, the core theme remained, that the world can be sampled and catalogued in a manner that removes phenomena from the context in which they emerge.

The world is viewed in this approach, not from a given location, but from an imagined ‘view from nowhere’ (Nagel, 1986). It is troubling, that this view happens to have supported the interests of Europeans, mostly rich male Europeans.

As Europeans began to extract short-term profit, robbing the world of its resources, they also viewed people as things to be exploited.

Western psychology has been developed around the tasks of observing measuring, defining, controlling, and managing people (…and marginalising some of them). People, as viewed by these psychologists, have given observable properties. They can be measured and categorised, as belonging to a specific culture, having a given gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and so on.

In this sense, you do not need to cross a national boundary to become a ‘foreigner,’ you just need to be defined psychologically as belonging to a minority group.

You are positioned as ‘other,’ as not belonging, as strange and different.

Martin Heidegger challenged the idea that things in the world are there, present, ready for us to observe from a dispassionate position (Heidegger, 1927). He was another theorist who made questionable life choices, joining a fascist and racist political movement (Bakewell, 2017). However, his writings help us by explaining how it is that we are already taken up in the world by our concerns.

Things come to hand for us when we want to do something. Their meaning and their value are implicit, revealed by the way we use them. In our everyday ways of being, tools are not things that we stand and contemplate as definable objects. They come to hand in our unthinking routines of getting through the day, doing what everyone else around us is doing. We can lose ourselves in these habits, where the truth of our existence is hidden behind unexamined assumptions.

How we see things and what we do with them are not phenomena that stand out. They do not show up easily as something that we might collect and put on display in a cabinet. They are just the unnoticed fabric of our way of being.

For example, a river in a wooded valley is for some people just the background to their meaningful existence, something that has sustained their ancestors, something which can enabled their future. If that is, it is treated with respect.

Others can only see the potential to cut down trees to sell as lumber, or the possibility of a dam in the river which would generate electricity (Heidegger, 1977). Technologies can, in this manner, make our lived-world uninhabitable.

We will only miss what we had when it is gone.

As psychological therapists, when we work with clients who are very much like us, it is hard to notice our assumptions or understand what we are doing. However, if our client is from a different culture, it will be easier to identify and suspend those assumptions.

We might then realise the mistakes that we are making.

We might notice how it is that people are often imposing assumptions and trying to assimilate others into their own world view.

Globalisation

Human distress is most often viewed in Western cultures as a kind of mental illness.

Western diagnostic systems are like a cabinet of curiosities. A box in which to place each condition, with its label and description.

Psychologists will ask: ‘What is wrong with this person?’, and where should we place them.

They turn to the methods of empirical science to find out how to ‘fix the problem.’ How, that is, to make the person function again as a productive member of our commercial systems. In contrast, phenomenological approaches offer the possibility of understanding what is happening from a human perspective.

Practitioners use reflexivity to explore the reality that each of us is always located somewhere in the world, driven by specific motivations. People are distressed by what is happening in their lives.

People are not something that we can take out of the world and examine as if they were an object.

We are flexible, learning and changing, in response to what happens to tus.

Distress can then be understood as most often the discomfort of being positioned, labelled, controlled, and managed.

Economic forces are unleashed across the world, increasing migrations and cross-cultural encounters. More and more people are confronted with the disturbing reality that their traditional ways of being, in their cultural heritage, are just one way of doing things.

One amongst many.

The blind rationalism of multi-national economic systems threatens to strip each of us of our unique humanness. Western psychology is a part of this when narrow definitions of mental illness are exported and imposed.

In contrast, freedom and choice are core themes in existential theory. As horizons are broadened in cross-cultural awareness, freedoms expand and contract. We become aware of greater possibilities in our options, in the way that we might choose to live. While we might also notice how we are at risk of moving towards a homogenised and narrow commercialism.

In societies where we shame people who are different, everyone is trying to fit in. They are trying to be ‘normal,’ whatever that is. They are following the latest trends, which are usually set by the rich and powerful.

Cultures are appropriated as commodities. The ‘exotic’ has a value, and it becomes something that requires additional payment, in holidays, products, and identity politics. Some people who are economically-disadvantaged must then package their culture and its customs, to sell to foreigners.

Otherness is exploited again, turned into entertainment and amusement.

In phenomenological understanding, we recognise that our knowledge-construction is never free of human interpretations, desires, and intentions. It is essential therefore that these emotional engagements are examined in research processes.

Care can be taken to promote an ethical framework.

With this reflexivity, it is possible to ask: ‘What is it like to have a specific human experience?’, and to use empathy to ease ourselves into an understanding informed by those who are having that experience.

We are not then treating people as things to be measured, fixed or used.

In existential therapies, we are meeting our clients as people, not as objects to treat, fix, change, or process (Buber, 1937).

If we are meeting our clients, then it is likely that both the practitioner and the client will learn and be changed by the encounter.

If existential theory and phenomenological practice are to be taken up in South-Asian culture, then there needs to be a meeting between people who will learn from each other. This is not a psychological therapy which requires that one party is assimilated into the culture of the other.

Both parties will find out about themselves, as much as they will find out about the other.

Phenomenological research attends to the human condition and this will have certain givens across cultures (Yalom, 1980).

We are all embodied, we all interact with other people, we all make choices, and we all die.

Beyond those aspects of existence, which we all share, there are significant cultural differences, which we need to acknowledge, reflect on and respect.

Perhaps there are theorists in Asian culture who have also asked: ‘What is it like to be human?’, theorists who have lived more enlightened lives.

References

- Bakewell, S. (2017). At The Existential Café: Freedom, Being & Apricot Cocktails. Penguin-Random House.

- Beauvoir, S., de (1949). The Second Sex. Trans. H. M. Parshley. Vintage Classics

- Buber, M. (1937). I and Thou (S. Verlag, trans.). Bloomsbury Academic. (2013).

- Heidegger, M. (1927). Being and Time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, trans.). Harper & Row.

- Heidegger, M. (1977). The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays (W. Lovitt, trans.). Harper & Row.

- Jaspers, K. (1932). Philosophy, Vol. 2: Existential Elucidation (E. B. Ashton, trans.). The University of Chicago Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1964). The primacy of perception and its philosophical consequences (Trans. J. M. Edie. In J. M. Edie (Ed.), The Primacy of Perceptions: And Other Essays on Phenomenological Psychology, the Philosophy of Art, History and Politics (pp. 12-42). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The visible and the Invisible (Trans. A. Lingis). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Nagel, T. (1986). The View from Nowhere. Oxford University Press: New York.

- Sartre, J-P. (1943). Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology. (Trans. H. E. Barnes). London: Routledge

- Seymour-Jones, C. (2009). A Dangerous Liaison: A Revelatory New Biography of Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre. New York: Abrams.

- Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. Basic Books.

Working with Stuckness in the Room

I stare at the clock as the minutes crawl by, feeling trapped in a groundhog day. No matter what doors I try to open, each one leads to a dead end or resistance. I want to do something yet feel powerless, any momentum halted by a wall I cannot seem to break through. Self-doubt creeps in that I am not good enough. I question if what I am doing is even making an impact at all.

You could be resonating with this in your life.

But what if I told you that this was my experience as a therapist in one of my sessions?

That’s right, therapists can get stuck too.

When she first walked into my office, she grappled with motivational issues and lack of career direction. Paralysis had set in. On paper, she was thriving - steady career progression, income well above his peers. But she just couldn't make decisions. The inertia was palpable.

2 years later, while her tendency to freeze in the moments of decision-making still lingers, her ability to cope with these moments have also become more sophisticated. Drawing healthier boundaries, increasing self-awareness, becoming more sensitive to her own needs etc.

Yet, in the last 6 months, I found myself feeling stuck in our work together. We would circle around the same issues about her inability to make bold decisions in her career. Her guilt around missed opportunities and her struggle with lost time.

I begin to feel tired, frustrated, or uncertain on how to move forward. I dreaded our sessions, questioning if therapy was even helping. Yet, I was reluctant to give up on us since.

Relationality

Relationality

In a moment of desperation, I leaned into this stuckness. I admitted to not-knowing what to do with us. To my surprise, she expressed feeling exactly same way. She revealed sitting in the waiting room each week, wondering if sessions are still helpful.

But is this a feeling she can even talk about it with me? She assumed that I knew what I was doing.

After all, I am the therapist here right? I should be the expert here. So she left it to me to decide what direction we should take in existential therapy.

Ah ha!

It is this recognition of our shared experience of stuckness that led us to start moving again in therapy.

This movement is a felt sense in the room. The space between us no longer feels claustrophobic. This is no longer a space of stillness and struggle. There is once again lightness and possibility in the work we are doing. Now an energy of flow moves between us. Our conversation feels open and energized. And more importantly, it feels like time is moving again towards the future.

Nothing has changed. My client still has not solved her procrastination problem. We still do not know how to work on it for her.

Our Existence Validated When We Are Encountered

However, it was in our encountering each other, human to human, in the present moment, that we recognise we are not alone in navigate this stuckness. It reminds me of a phrase that an Dr. Miles Groth, an existential analyst, once said, “being encountered is the initial moment of every instance of existential .”

Existential validation if the mutual conferring of us being human be-ings through as simple as a gaze, touch or speech.

Knowing that we share the same subjective reality with someone and to decide to walk through it together can be a powerful healing experience…even if we have not found a way out yet.

Yalom’s often-quoted thought beautifully captures this spirit: "It’s the relationship that heals." (Yalom, 1989, p. 91).

How Does Existential Therapy Work with Stuckness in Life?

Existential therapy is fundamentally relational. Existential therapy may be based on a set of philosophical ideas but it is objectifying to be using a theoretical lens to view my clients. Instead, being relational means meeting my clients as a human being first; as a therapist second.

It is to engage in the here-and-now dialogical relationship between the two human persons where we flexibly attune to the each other’s relational needs In the therapy room, the therapist dances between focusing on the client, reflecting internally, and attuning to the relationship. This fluid dance leads to a deeper understanding of the client's subjectivity.

This is what happened in that particular session with my client. As I attuned to the stuckness in our therapeutic relationship and offered it as a discussion in our session, we uncover the parallel of how the stuckness in her daily life is repeated in the therapy room.

This relational way of working together reveals a key principle in existential psychotherapy: therapy is a microcosm of our social world. What happens in the therapy room often reflects processes occurring in our daily lives and relationships.

Understood in this way, the power of existential therapy in working with stuckness is neither teaching the client a set of new techniques nor encouraging them to change their thoughts or behaviors in a prescribed manner.

To learn more about Existential Therapy in Sinagpore and Aisa, visit our homepage.

What Does an Existential Crisis Look Like?

Existential crisis is like a call from our soul. It is calling out to us to live more meaningfully.

As long as we are humans, we can't avoid going through an existential crisis.

Even psychotherapists do. In fact, I went through one myself in 2020.

Let's walk down memory lane.

Lockdown in Singapore

2 weeks into our circuit breaker in 2020, Singaporeans find ourselves having to endure another 4 weeks.

Why can’t the government just call this circuit breaker a lockdown like other countries?! I want to loiter around aimlessly, why can’t I?! There is nobody on the streets, why do I need to wear a mask?!

These were some of the questions I was asked in the first two weeks. At the time, I had the inner resources to fend myself from these frustrated-filled outbursts from the people around me.

Hope. I had it.

This was going to be like a retreat. Finally, some time to myself! A luxury I’d been yearning for since the beginning of my doctoral journey anyways. No work. No problem. I will just need to spend less. I have supportive family and friends. I have a direction in my life- writing my thesis and setting up my private practice. All is set, what more do I need for these 4 weeks?

But, hope can be such an elusive thing. I had it but it can be taken away so quickly at the same time too.

Precisely at the moment when I found out that our remaining 2 weeks had extended itself to 6.

Now I find myself asking those questions as well.

This is an existential crisis we are all in.

People are dying without their loved ones to send them off on their last journey. We have to make lifestyle changes that we would prefer not to. Parents are anxious that their children with mental health issues are going to be caught not wearing their masks on the streets yet they’re limited by what they can do. Elderlies are suffering from insomnia, triggered by anxiety and worry, but do not dare go to a hospital for fear that they may get affected themselves. Children are forced to consider balancing risks with concern about their demented parent’s welfare in terms of isolation and lack of stimulus way before the circuit breaker kicked in.

Even for the people who are bent on not being defeated by it mentally or emotionally finds themselves affected by it one way or another. One poignant example is the mad rush for bubble tea before the stricter restrictions set in. In a way, it’s a death of some sort. Not the physical kind but we have to die to some of our desires, cravings and needs.

Useful things I have learnt from the Existentialists

Today, more than ever, humanity needs to turn to existential philosophy for wisdom and direction.

It’s a great reminder, especially now, that man exists.

And to exist in existential terms is not the passive ‘lying around’ understanding that many of us hold today.

The etymology for ‘exist’ in Latin is ex-sistere which means to ‘come into being’ or to ‘take a stand’. This standing out takes on an active feel that contrasts sharply with the passivity that comes with saying ‘unicorn exists’, meaning that unicorns are lying somewhere in the world waiting to be found.

As active agents in the world, we are not bound by our essence or a fixed nature which goes on to set our purpose or function in the world.

As Sartre said, man is not a manufactured thing. Instead, our existence is a dynamic one where we are capable of going beyond ourselves.

Yet, today, my authentic selfhood, and probably for some of you here too, has been thrown into the limelight once again and up for scrutiny as I question what it means to be myself in these crazy times.

Authenticity as ‘an openness to existence, an acceptance of what is given, as well as our freedom to respond to it’ given by Hans Cohn may become, paradoxically, inspiring and empty at the same time for some of us.

We may have the intention to transcend ourselves, as existence necessarily calls for. For me, I want to commit to being a better student, counsellor, friend, wife or even just a better human being. I believe fully in being the author of my life, fulfilling my responsibilities with the resoluteness and passion that existential philosophers like Heidegger and Kierkegaard had talked about.

Yet, the hardest part is not in commitment but it is more so that the extended restrictions that stops us from giving our wholehearted yes to life in the near future.

For many of us, the existential crisis lies in how to move forward with our lives.

How should we even start making sense of 2020?

However, these existential philosophers also remind us that existence is not an individual endeavour.

We live in a world. This world is not just an environment that is independent from those who talk about it. The word ‘world’ comes from the Old English compound, weor-old, and taken etymologically, it means the ‘age of man’. As such, when we talk of us living in the world, we have to take into consideration that the human factor is essential in our concept of the world. Our existence is impossible to be apart from other people. In other words, we need others to exist.

Yes, existentialists are wary against people who lose themselves in the ‘herd’ or ‘crowd’. However, funnily, the hyphens in Heidegger’s being-in-the-world serves as a solace for me as well, especially at this time where I am reminded that we do not live in isolation.

Existentialism is not as individualistic and despairing as it seems to be. Man exists as persons only in a community of other persons and no authentic existence can lack a social dimension.

Reinterpreting Mick Cooper’s words in his book Working at Relational Depth in Counselling and Psychotherapy, an authentic being-with-self can only be obtained while being-with-others.

In the midst of losing my mojo, I appreciate my existential philosopher friends more so than over. As I read their work, I am called to appreciate the solidarity that I have witness so far in the local community where friends are reaching out to one another in inventive ways like zoom lunches and the public volunteering themselves in their own ways to support those needing an extra emotional or mental boost.

At its core, existence is paradoxical.

Authentic selfhood requires the exercise of individual freedom, will and decision for its attainment.

Yet, at the same time, we can only exist as persons in the world with others. This inherent paradox in an authentic existence becomes all the more prominent now with our second wave of restrictions.

And the existential question many of us could be asking as a society and as a human race at the moment is:

How we can continue to exercise our freedom, will and creativity, being the active agent that existence requires of us, while not being swallowed up by the new restrictions that are continually being rolled everyday (for good reasons)?

I don’t yet have an answer. And maybe I don’t need one. I don’t know.

But I’d like to think that the question is a hopeful rather than a despairing one.

Coping With Anxiety

Living with anxiety can be very tiring.

At this time, it is important to look after your physical health, practice good sleep hygiene and form strong and healthy support networks. Keeping up with a meditation practice or even just practicing breathing exercises has shown help some of us cope and feel more in control. Apps like Headspace or Insight Timer have many simple and easy-to-follow guided practices that are especially useful for beginners.

One may say that I have tried all these ways of coping with my anxiety but nothing seems to be working. This place feels helpless and vulnerable to some of us while it may feel bleak for others.

Yet sometimes, it is not so much what we are doing that is not helping. It is the attitude we go into doing these activities that needs some adjustment.

1. Having a different relationship with anxiety

In the article on existential anxiety, we mentioned that anxiety is part of being human. Whether we are conscious of it or not, anxiety is present in all of us. There is a purpose to all emotions, anxiety included. Anxiety is those up swinging emotions that makes us want to do something about our lives. It gears our body up for the things we aspire to achieve. It can be seen as a creative energy that challenges us to be more inventive with how we want to go about life.

Seen in this perspective, anxiety is not something to be eliminated but merely managed. We have to reconsider if anxiety deserves to be thrown away since it can be good for us. Rather, it is more about sitting more comfortably with anxiety, letting it to teach us what life is asking of us while not allowing ourselves to be overwhelmed by it.

Sometimes, when we are overwhelmed by feelings of anxiety, we feel like it is all we can think about. Our anxiety becomes us and we become anxiety.

The Buddhist teaching of bearing witness can aid in our awareness that we are more than just our anxiety. It allows us to say

‘I feel anxious. I have anxiety. I am being anxious. But I am not anxiety. I am more than my anxiety. ’

Some of you may be wondering, ‘how does this work?’

Try to imagine this: you are looking at a cloud in the sky. You who notices the cloud is not the cloud but the observer. Next, move your attention to another object around you. The fact that you can identify it means that you are not the object. This is the same with our anxiety. When we watch anxiety come and go within us, we become witnesses of the emotion. We are not the emotion.

This is a healthy way to look at anxiety or even other difficult emotions as it allows us to honour its presence. Yet, we do not need to identify ourselves as anxiety. Our lives are more than just our feelings. We are also formed by our values.

2. Write it down

Can you allow your anxiety to motivate and guide you to a more authentic and purposeful life? What can your anxiety teach you about your relationship with yourself, others and your world around you? Jotting all your thoughts and feelings about these questions in your journal can be a helpful way to find out how to cope with your anxiety in your own unique way.

3. Talk to a therapist

When you have exhausted all the options and none is not helping, you can consider seeing a therapist or counsellor. There are many forms of therapy out there and each therapist works differently with their own style and specialization.

For a very general idea of how different therapy works, you can read the previous article on 'Do all therapists work in the same way? How do I choose my therapist?'

There are a few types of talk therapy that we recommend for anxiety issues:

- Existential Therapy- specializes in helping clients to reconnect with their meanings in the face of anxiety. See our article on 'There is no one way to live' for more information about this kind of therapy.

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)- specializes in helping you understand how your thoughts, beliefs and attitudes affect your feeling and behavior. It teaches you coping skills to cope with specific issues.

- Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT) - In simple terms, ACT is a form of therapy that helps individuals to focus on two key concepts -acceptance and commitment. It aims to help individuals accept what is out of their control (e.g. the presence of anxiety), and commit to actions that are in line with their values (e.g. going to a family dinner). Thus, the focus of ACT is not to change or reduce the frequency of anxious thoughts and feelings and bodily sensations, but to reduce the struggle with these experiences. The practice of ACT is also very much based on mindfulness, so ACT interventions could include the practice of mindfulness exercises.

- Art Therapy is a form of psychotherapy using the creative process in a safe therapeutic space to improve psychological and emotional health. It is open to all - art experience or skills are not required. It may be a transformative intervention for people with anxiety, especially if they have difficulties verbalising their struggles, or if they tend to be overwhelmed by emotions or ruminations.

- EMDR Therapy is the therapeutic intervention recommended when anxiety and panic attacks stem from traumatic experiences and memories. EMDR stands for Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing: it is an evidence-based modality used to address adverse life experiences that contribute to disruptive symptoms in present living.

Who Can Help?

Encompassing's Services

Specialising in providing individual and group therapy services to those who are going through major transitions in life.

Schedule a First Therapy Session with us

The start of your journey to healing. In this Introduction session, you will meet and get to know your therapist, and allow them to get to know you too. This is a good time to get a feel of what working together will be like and if you feel comfortable in the presence of the therapist. The therapist will tell you more about Existential Therapy and what a session is like, as well as field answer any questions you may have about therapy.

You will also get to chance to voice what problems you are facing and the therapist will be able to give you some guidance about how therapy can help.

This session is 50 minutes long and must be booked in advance.

Available in clinic or online.

$220 per 50 minutes

Other Useful Contacts

Counselling Helplines

Samaritans of Singapore (SOS)

24-hour suicide prevention hotline- 1800-221 4444

10 Cantonment Close #01-01

24-hour emotional support to those in crisis.

Institute of Mental Health (IMH)

24-hour hotline- +65 6389 2000

Offers a range of counselling and rehabilitative services to people of all ages

Tinkle Friend helpline (by Singapore Children’s Society)

1800-274 4788

chat online at www.tinklefriend.com (for primary school children)

Affordable Counselling

Clarity Singapore

(65) 6757 7990, ask@clarity-singapore.org

Helps people to cope with mental health conditions arising from anxiety and depression

Care Corner counselling Centre

Hotline 1800-353 5800 (for Mandarin speaking clients)

A non-profit, charitable organisation offering counselling services for lower-income families across Singapore.

Sage Counselling Centre

+65 6354 1191

Specialising in counselling services for the elderly (aged above 50) and their caregivers

Private Practices in Singapore

Colourfully Pte. Ltd.

Colourfully offers art psychotherapy and EMDR therapy for adults.

Lotus Therapy

www.lotustherapy.com

Founder of Lotus Therapy, Anita Barot is a licensed marriage and family therapist. Her expertise involves working with couples, parenting, and women's issues.

Insight Therapy Services www.insight-therapy.com.sg +65 8115 5362 | Alex@insight-therapy.com.sg Provides adult ADHD, Behavioural addictions (gaming & Sex) & EMDR therapy.

Sofia Wellness Clinic

+65 83683591 | hello@sofia.com.sg

Sofia Wellness Clinic offers counselling and psychotherapy services based on positive psychology to teenagers and adults to help them overcome life challenges and flourish as individuals.

Soulmosaic

+65 8798 4519 | office@soulmosaic-therapy.com

A practice offering multilingual therapists and a safe, compassionate space to recover strength, resilience and joy

The Psychotherapy Clinic

www.thepsychotherapyclinic.com.sg

+65 8828 4006 | simonneo@thepsychotherapyclinic.com.sg

A private practice with a desire to BRIDGE TRUST and BUILD HOPE into the lives of those that are challenged in their current life station.

Reflections: How Did I Become an Authenticity Researcher?

For a long time now, I have always wondered if authenticity and being Asian are compatible.

Having grown up in Singapore and coming from a traditional Chinese family, I’ve been taught to greet my elders and respect authority figures. We have a saying in mandarin, ‘ 入得厨房 出得厅堂’. It means that an ideal woman is one who can perform diligently in all household chores and yet act as a proper lady who knows how to dress elegantly, has graceful and polite manners and is able to hold mature conversations in social settings.

Training starts at a young age. And through my clinical experience, I notice that I am not alone. An experience I share with many of my clients are the unhealthy labels that we carry with us since childhood: Crying is shameful. We are selfish if we do not share our toys. Talking back to our parents is a sign of disrespect.

The common message across these labels is that we should care for others above our needs.

This is where I struggled with the modern idea of authenticity (see article). If being authentic is defined as staying true to ourselves, essentially being congruent, sincere and transparent, how attainable is it for Asians who ultimately values collectivism over individualism?

It made me wonder if authenticity is only reserved for the western world. I had a hunch that it was not exclusive to only certain groups of people. It should be a universal human value.

I had another belief: It is when we throw the baby out with the bath water, pitting being true to ourselves against being around for others, that problems arise. Looking back at my own life and with my clinical experience, I notice that anxiety, depression and other mental health struggles arise when we perceive the tension between having our voices heard and experiencing a sense of belonging with others to be unsolvable. However, our true voice and our sense of belonging should not be an either/or experience but a both/an.

Even then, there were still many other things I did not know. How will authenticity look like in an Asian society? How can I be true to myself without throwing away my Asian roots? Should I respect my needs first or others? After all, Asian values like harmony, benevolence, righteousness, courtesy, loyalty, and filial piety are not undesirable.

It is with these burning questions that led me to become an authenticity researcher 5 years ago. I hope that my work in attempting to conceptualize an Asian interpretation of authenticity, starting with millennials, will contribute to the mental health of the young people in Asia.

Authenticity: Is Being True to Ourselves Enough?

What do you think of this necklace?” the wife asked. It was a thin silver chain with a dark, large stone encased in silver.

“I think it’s gaudy, something my grandmother might wear,” the husband replied.

What is your first response if you were the wife?

The husband here is Dennis D. Waskul, a professor at Minnesota State University. Interested in the topic of authenticity, he designed his own Garfinkelian social experiment, where he would be completely honest to himself and others for an entire day. This was his authenticity project.

Authenticity is a buzzword these days. We use it in the field of leadership, tourism, experiences, food and many more. We cannot deny it has become an important value in our society. Even for those of us who do not explicitly use the word, phrases like “be true to yourself”, “be who you really are”, “follow your heart”, “be yourself” or “express the real you” will not be unfamiliar.

Behind these phrases is an assumption that our inner self is the true self and the outer self is just a mask. To be authentic is to make our outer self more congruent with our inner self.

I grew up in this culture as well. I believed it. However, simmering beneath the surface was always some kind of anxiety, guilt and doubt. I often found myself struggling to express myself to others with full honesty. My mind would tell me that it is okay to be honest with what I thought but my body screamed, “Danger!” What became easier for me was to wrap uncomfortable truths in pretty packages – I often wondered if telling these truths as they were might upset the people I was talking to.

So just reading Dennis’ day of expressing his true thoughts cracks me up endlessly. Yet, I am aware of my own anxiety around it as well.

It makes me question if the consequence of authenticity is pushing people away for the sake of being true to ourselves. Is this how it should be?

Here is another snippet of Dennis’ day.

“Dennis, are you busy right now?”

“Ah, well, actually YES.”

“Oh, I’m sorry…. Hey I have a student in the office right now, one of my advisees. He is having a hard time crafting the method sections for his qualitative study. I’m wondering if you’d be willing to meet with him, help work through his problems, and get ready to collect data. Could you do that?”

“I could but I don’t want to. I have enough students of my own. I don’t need to take on yours as well…. I am very busy, and you’re asking way too much of me.”

“Well, excuse me!” she says in a tiff, as she turns and walks away.

Clearly, I understand where the humour of it comes from. Few of us speak with so much honesty and transparency and it’s refreshing to hear others speak like that.

However, this invites us to rethink what authenticity truly means. Giving Dennis credit, he was being sincere. Sincerity, according to Lionel Trilling, author of Sincerity and Honesty, refers to a congruence between avowal and actual feeling. We would then need to ask ourselves if sincerity and authenticity are actually the same thing.

I’m ending this first article here, with more questions than answers because authenticity is deeper than what it seems.

I’m hoping that through the next couple of articles, you and I can explore different sides of authenticity. And as we emerge out of it, we can see authenticity in a new light. This time with more clarity and understanding.

Related Articles

What is Existential Therapy?

Existential therapy encourages people to embrace the reality of suffering in order to work through and learn from it.

Relationality

Relationality